To know the future we have to understand the past. And of course there is also history repeating itself.

Gustave Flaubert would have loved these two sayings and he would certainly have used them for his dictionary of received ideas. Flaubert himself noted down a cliche that has some relevance for this lecture. It goes

photography: will make painting obsolete.

Karl Marx used the one about history for one of his funnier quips: history repeats itself, first as a tragedy, second as a comedy.

Still, there is truth in both sayings. History – or humanity – certainly has a tendency to repeat itself and we can only recognize these repetitions and learn something if we have some knowledge of the past.

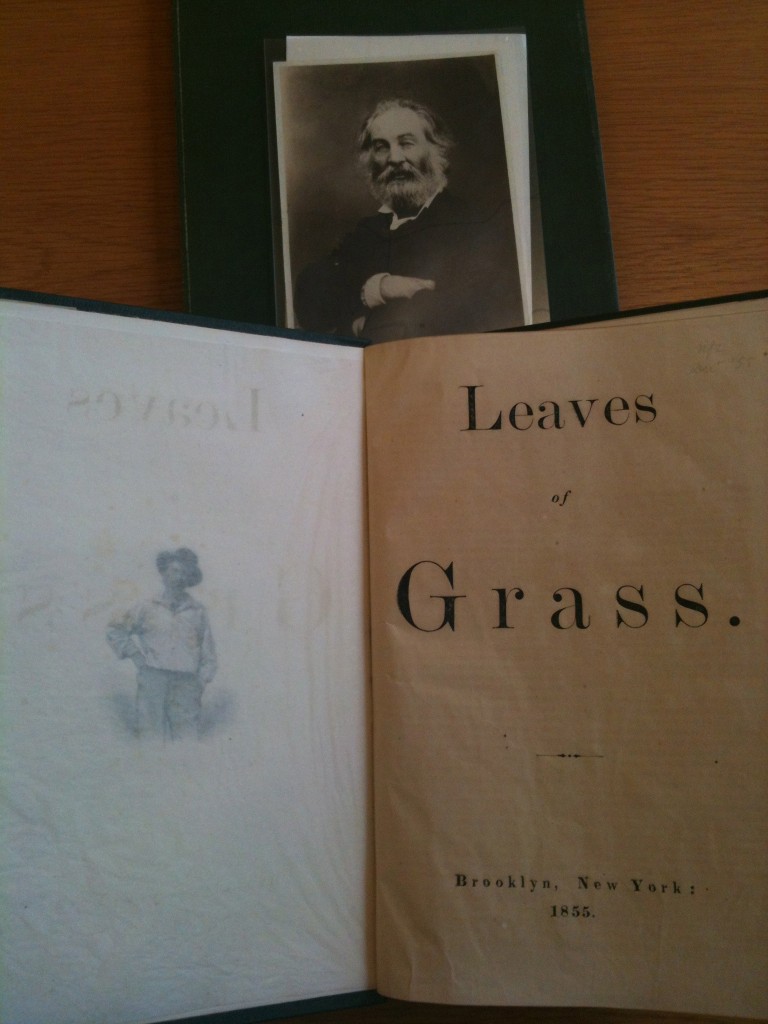

At the moment we are in the middle of one of the greatest sea-changes the world of information has gone through. Therefore I want to take a look at what happened during an earlier era and share some ideas with you about the lessons of history.

What can we learn from the 15th century change from manuscript to printed book? Does it tell us something about the fate of the printed book itself? What lessons might the early heroes of printing have for the internet publishers of our days – and of course for us bookhistorians who are going through such interesting times. I will say something about design but more about the financial circumstances that influence design. During my research for this paper I came to the conclusion that these circumstances are perhaps more important than changes in design we see on the page – and may expect to see on the screen of our digital books.

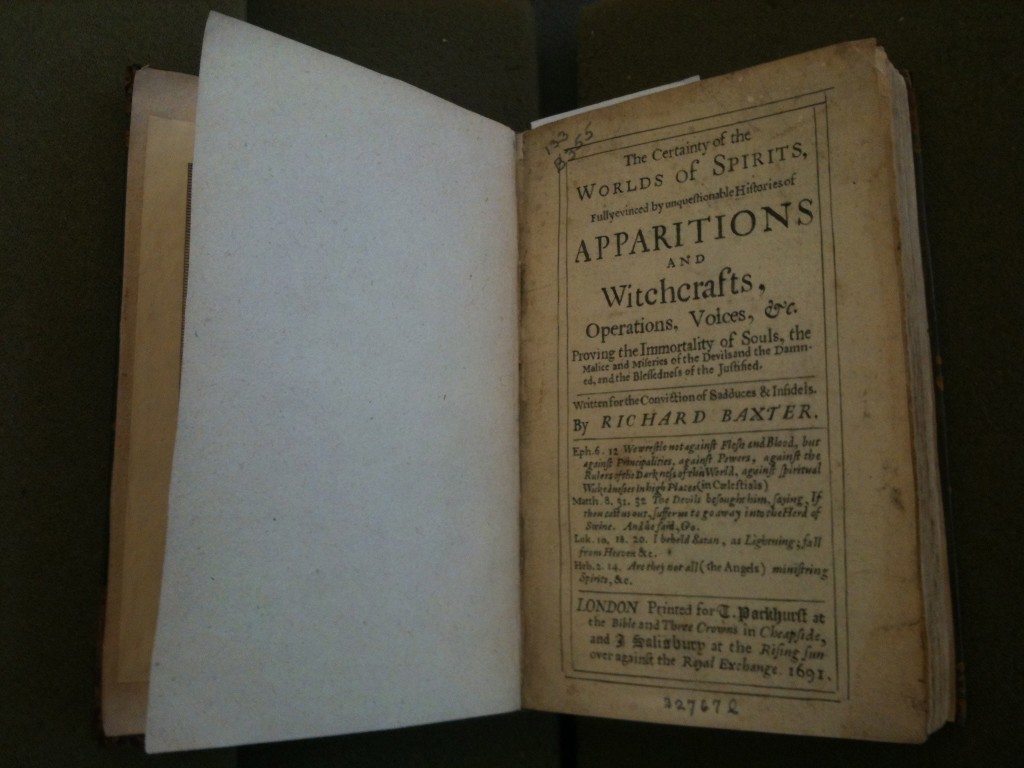

I consider the codex a far more important, interesting and influential invention than the computer or the internet. The codex has now reached a venerable age of more than 17 centuries. About a hundred generations have used it’s unique features.

There is a difference between a codex and a pile of papers held together by a pin or glue. The uniformity of the size of the pages defines the accessibility of a book. Quick and random acces to information, that is what the codex is about.

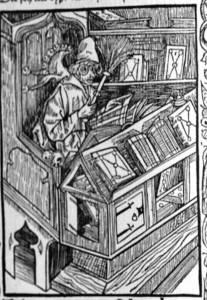

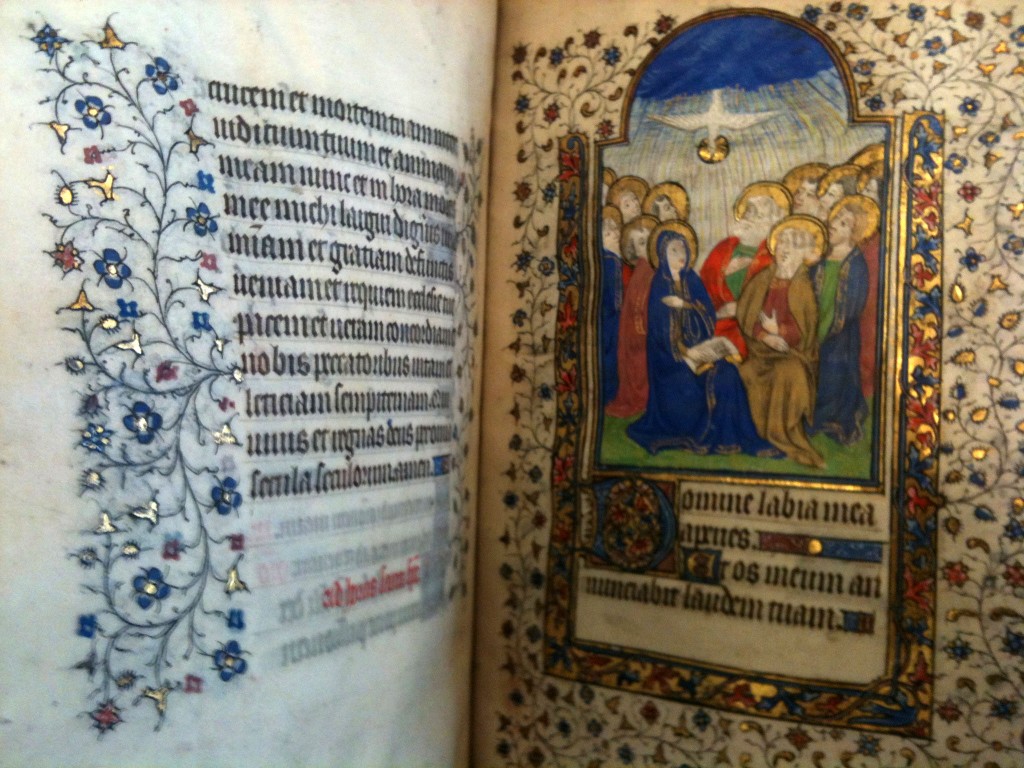

Creating such a book in the middle ages was everything but easy.

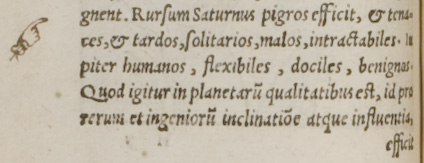

For a medieval codex you would have to slaughter ten or twelve pigs or sheep and have vellum made of their skins. After that you had to find that rarest of species: a man or woman who could write down a text for you. Early medieval society was hardly organized and places where you could have a book made or actually see a book where few. Monasteries were scarce and wide apart.

Secular reading – for instruction or pleasure – belonged to the city. To be able to live in a city and do something else than menial work, you would have to be able to read. Once you could read you probably wanted to read more than bookkeepers records. You wanted to read books. Religious books, scholarly books, adventures and poetry.

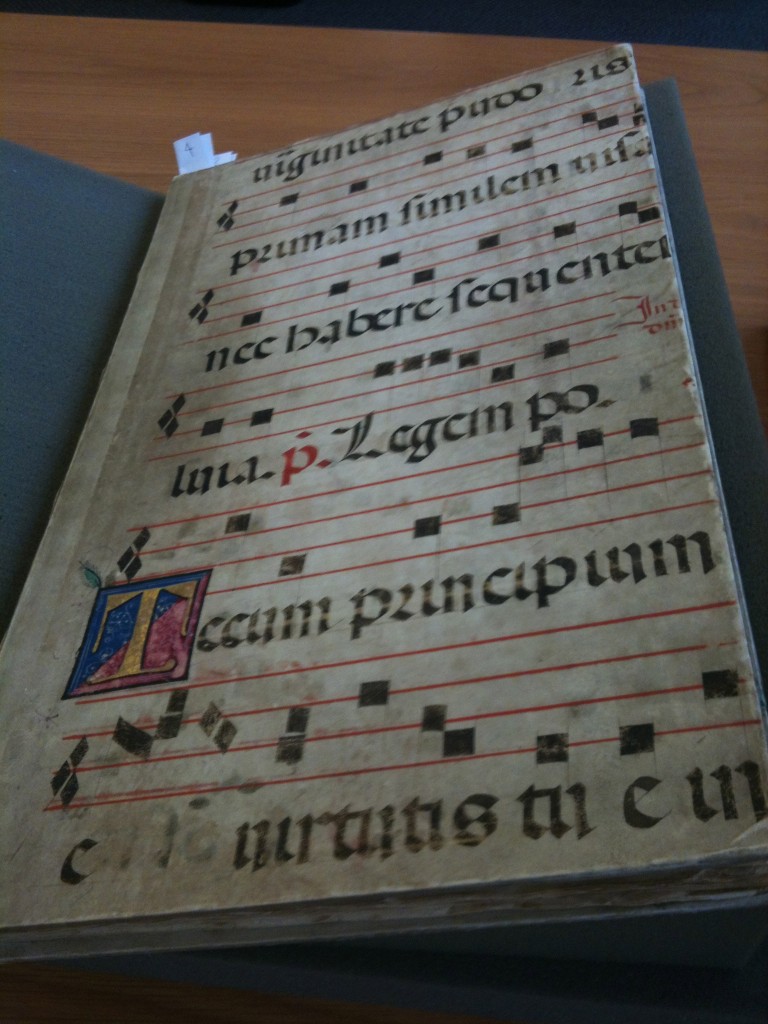

And soon an industry came into existence that catered for this new market of readers. Scriptoria in great cities like Florence where well organized companies that produced high-quality manuscripts for a decent price.

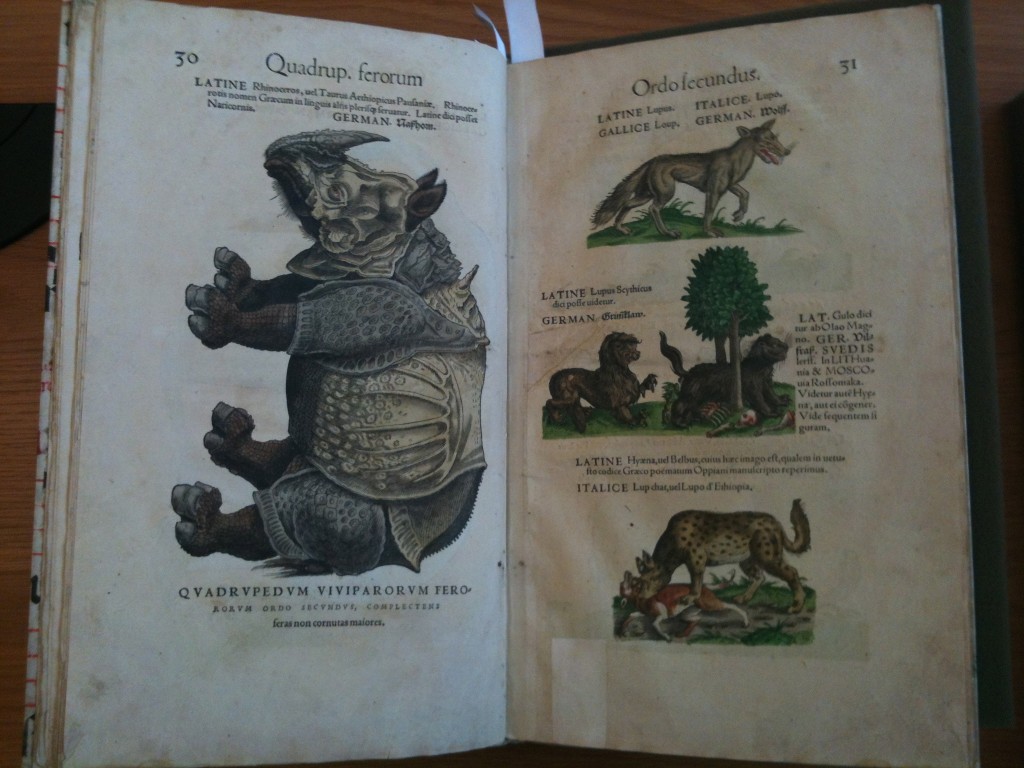

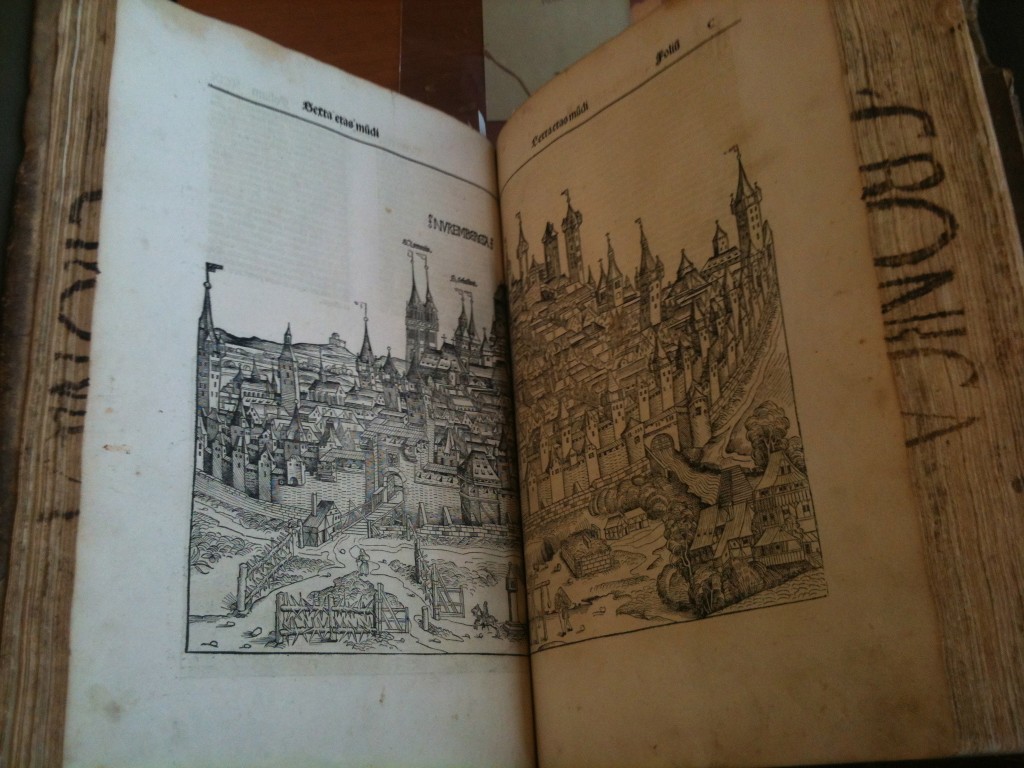

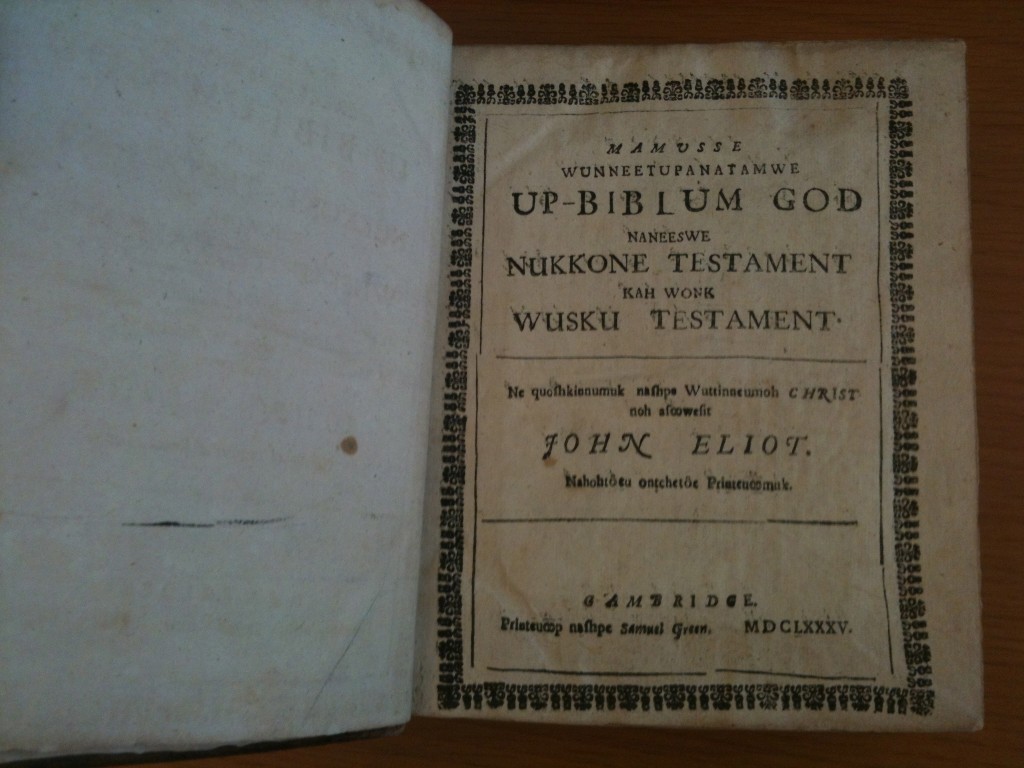

Then, halfway the 15th century came the printing press – invented by the Man of the Millennium, Gutenberg. More than 29.000 titles were printed up to 1500 are known today. If we put the number of copies of an edition on the arbitrary number of 300 this would mean that at least 9.000.000 books were made and sold during the first 40 years after Gutenberg.

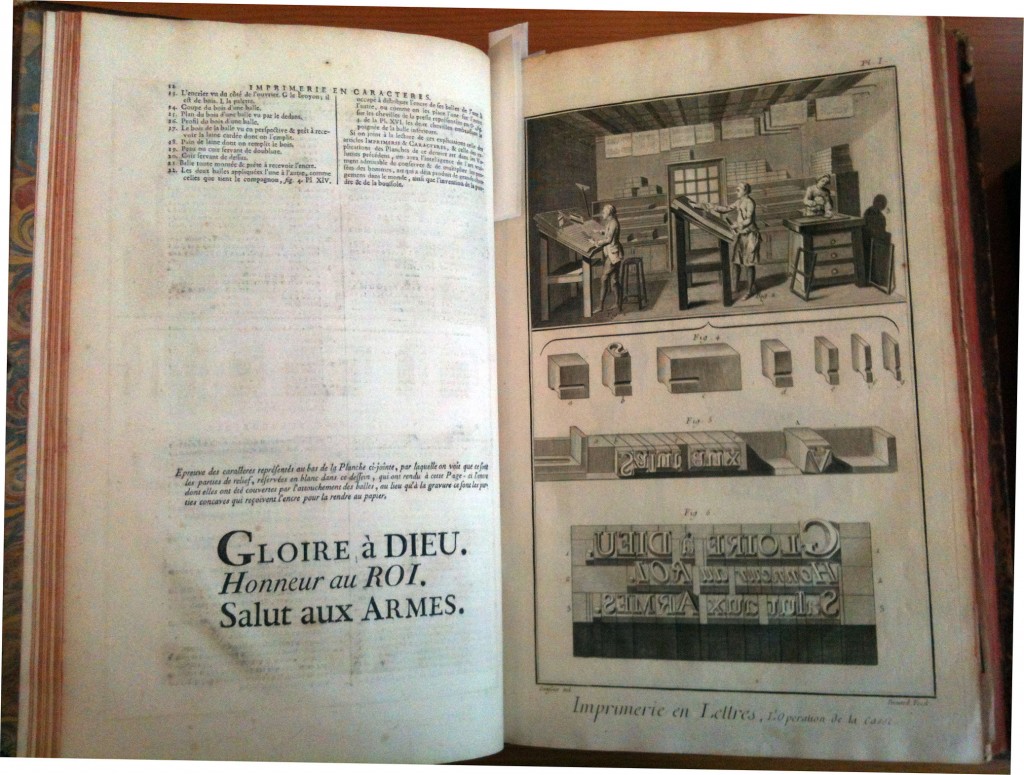

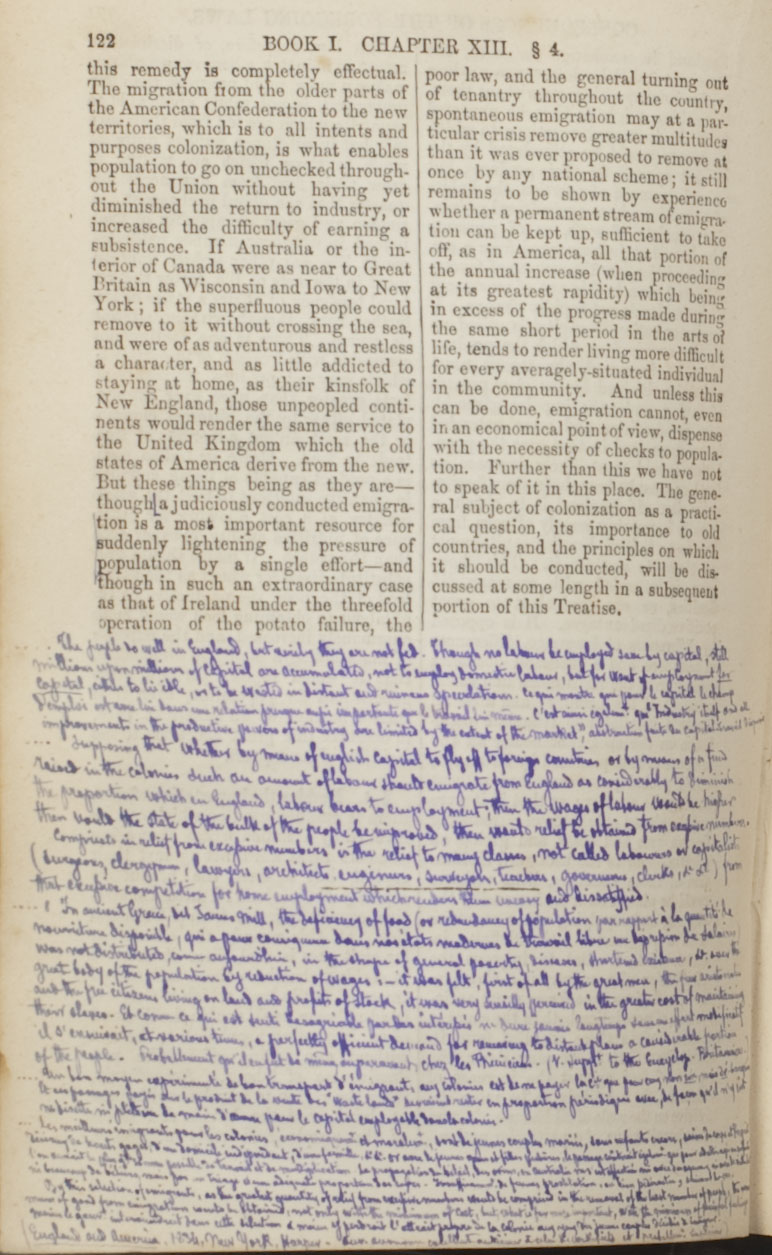

It is clear that here we have a genuine information revolution. At the same time it is a rather curious revolution! What everybody knows, but hardly anybody seems to realize, is that printers played a relative small part in the making of a book. In the days of Gutenberg the typesetters and printers realized far less than half of the value of a copy.

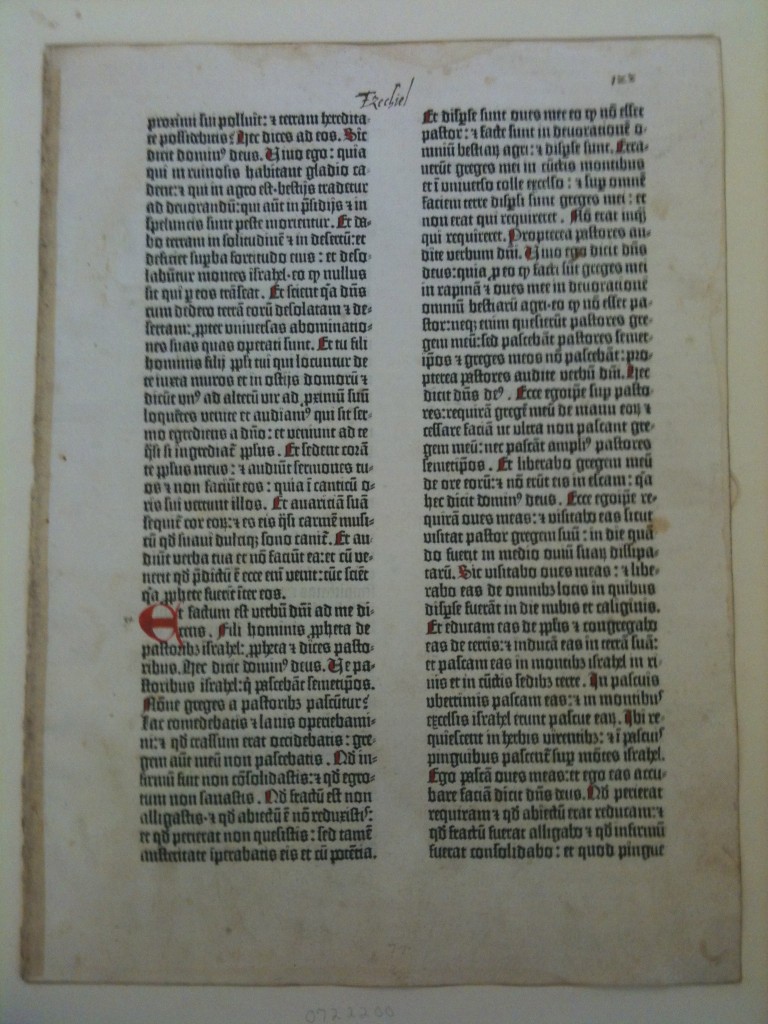

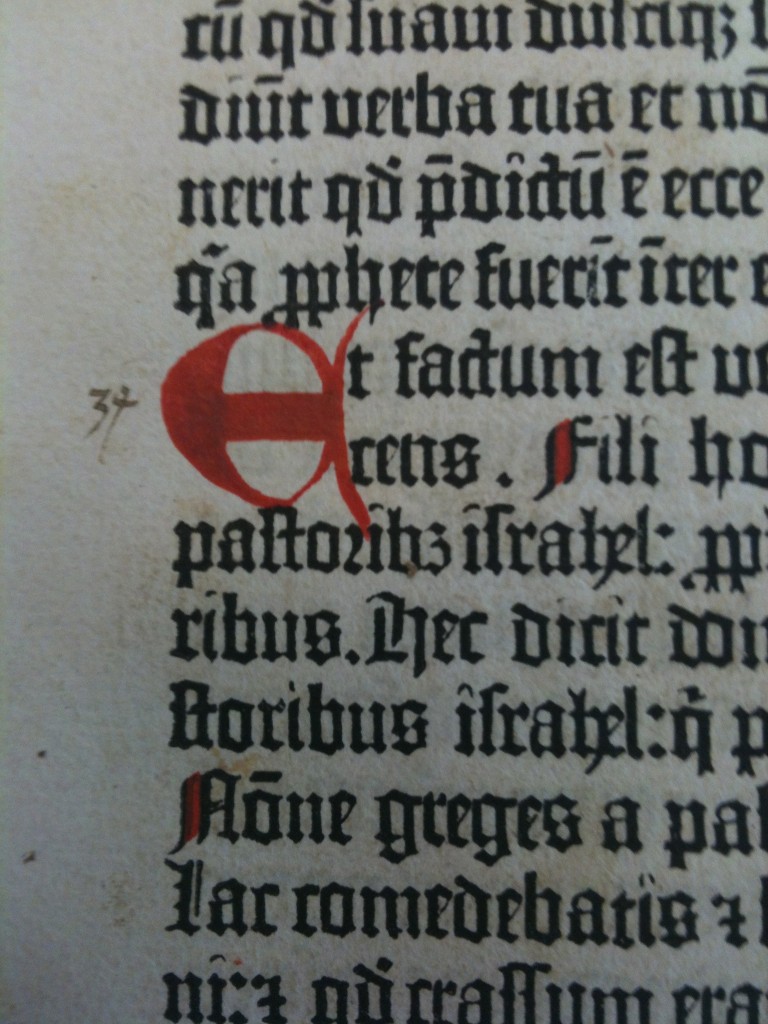

The materials of which books were made, claimed the major part, even when paper was about ten times less expensive that vellum. So the actual printing of a book may have been 50 times less costly than writing it down by hand, but the printers could only claim about 20% of all work done on a single copy. The rest was done – or supposed to be done – by rubricators, illuminators and bookbinders.

In the 15th century a paper copy of a printed book would be half as expensive as a handwritten one. It will be clear that the prime importance of Gutenbergs printing press lies in being a catalyst. Printers printed editions and editions had to be sold.

Gutenbergs artificial writing machine was certainly not meant to be a prime mover that made knowledge available to the masses and revolutionized the world. That kind of book emerged almost half a century later and was created by a totally different kind of man. The 40 years between Gutenberg and Aldus Manutius brought us the modern book.

The birth of the book as we know it is the result of typical capitalist development with its system of trial and error, fuelled by greed. It is important to remember that, while the price of a single copy of a book might be halved, the total investment needed to produce that copy as part of an edition would rise more than twohundredfold. The return of investment would be slow as it might take years to sell an edition. And before work on that edition could start, there would be an initial investment in the equipment of a printing house and the hiring of an expensive specialist workforce.

It was only in the 16th that being a publisher or even a printer became a sure way to riches. In the early days the infrastructure to sell 500 copies of a book was non-existent. Early printers seem to have thought and act like the makers of manuscripts. The first printing press in Italy was up in the mountains and days away from Rome. It was rather difficult to print in Subiaco and still expect to sell a lot of books in little time. So Sweynheim and Pannartz moved their bussiness to Rome. And even then life was difficult. To be able to sell books printers and publishers had to create a close knit community that was parochial and international at the same time.

The advent of the printed book made rubricating and illuminating a booming business and that is perhaps the reason why the quality of manuscripts detoriated so much in the last decennia of the fiftheenth century. It was only in the fiftheen-seventies that printers started to experiment with printed initials and woodcuts, thus streamlining the production and reducing the costs of a single copy with at least another 20%.

Aldus Manutius established his firm in the great merchant city of Venice, had sound financial backers and reduced the size and thus the price of books. But he hardly if ever used the woodcut initials that would have reduced the price of his books even more, although he did so in his most famous publication: the Hypnerotomachia.

It seems clear that most 15th century printers did not realize the real potency of the printing press and indeed saw it as a form of artificial writing. There was no break with the past. They saw their activities in no different light than the makers of manuscripts.

Even today paid writers exist who ply their trade on the streetcorners in Mexico or India. They write letters but also newspapers. The investment for such a trade is small. You have to know how to write, which may take some years to learn and that is it. I will come back to these writers later on when I will discuss the impact of the internet on the publishing industry.

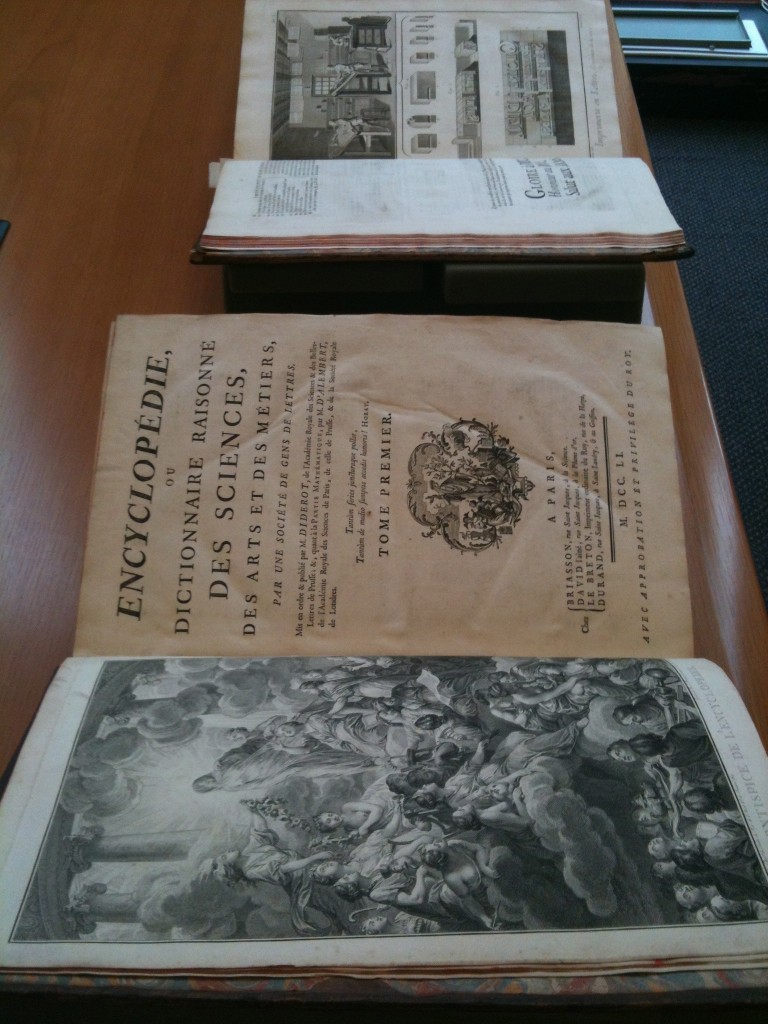

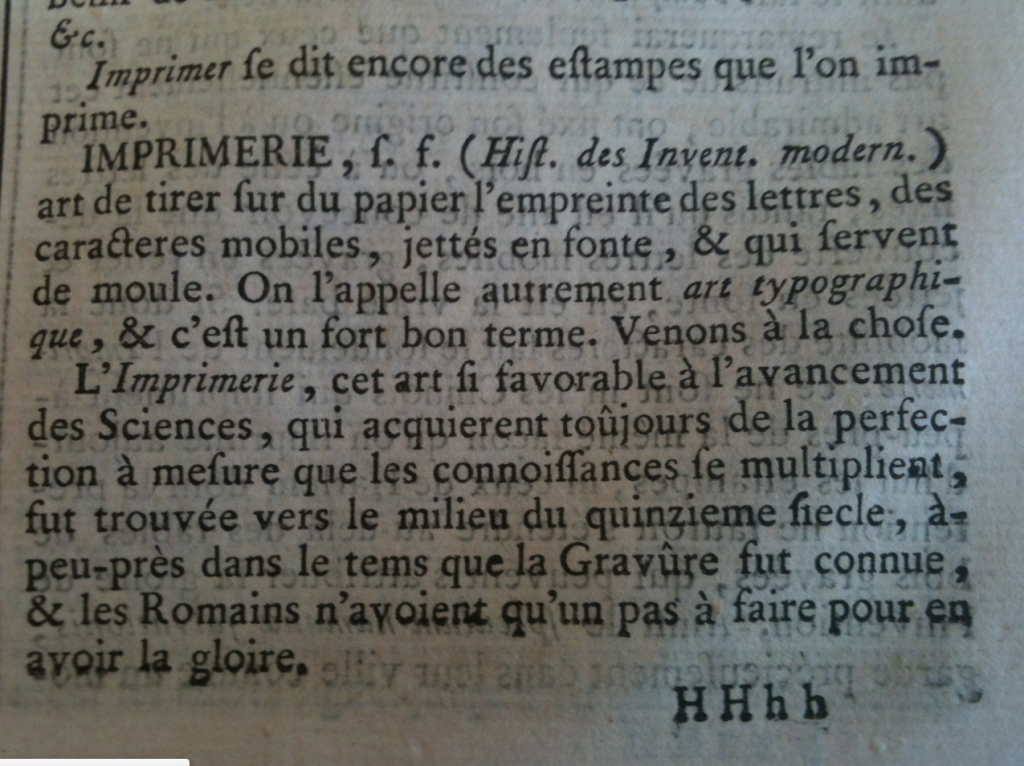

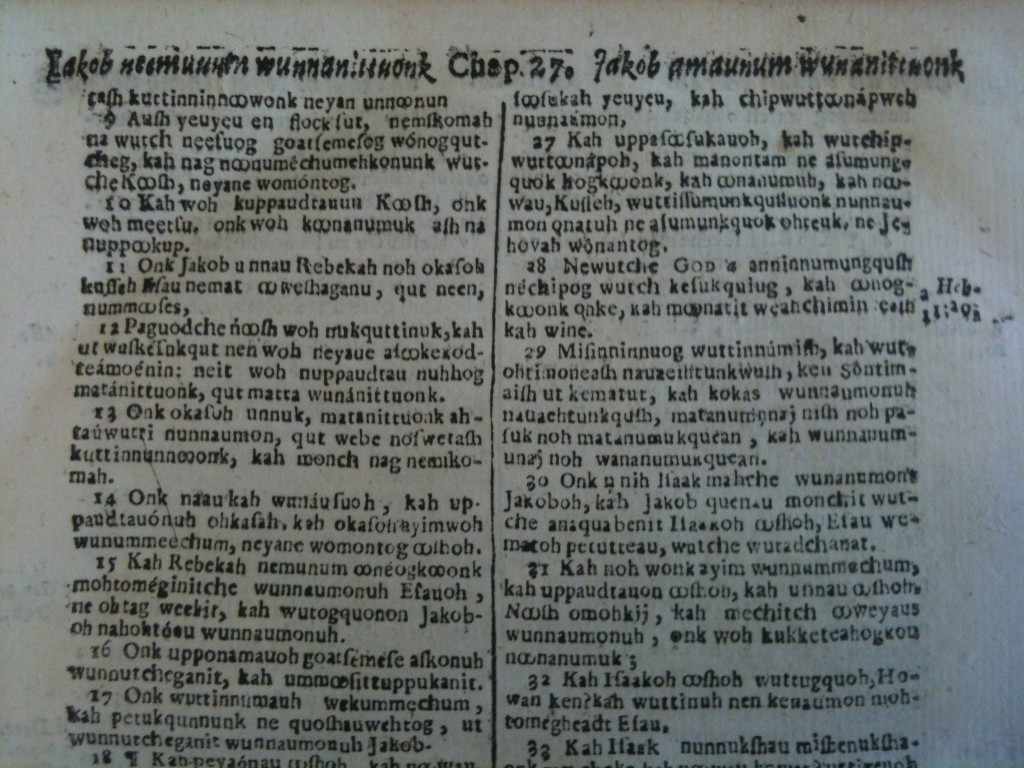

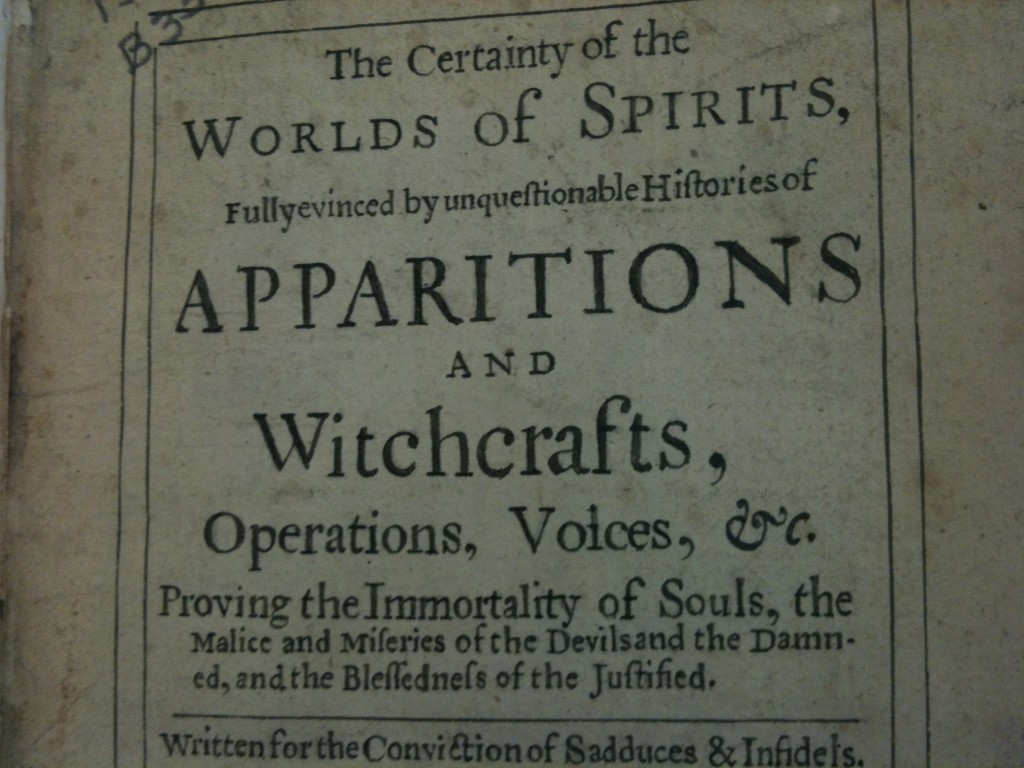

Many books have been written about how the layout of the page had to be reconstructed to conquer the oceans of information that suddenly became available. Pages had to be numbered. The paragraph had to be invented, just as notes and bibliographical references. Running titles. And most important of all: the title-page.

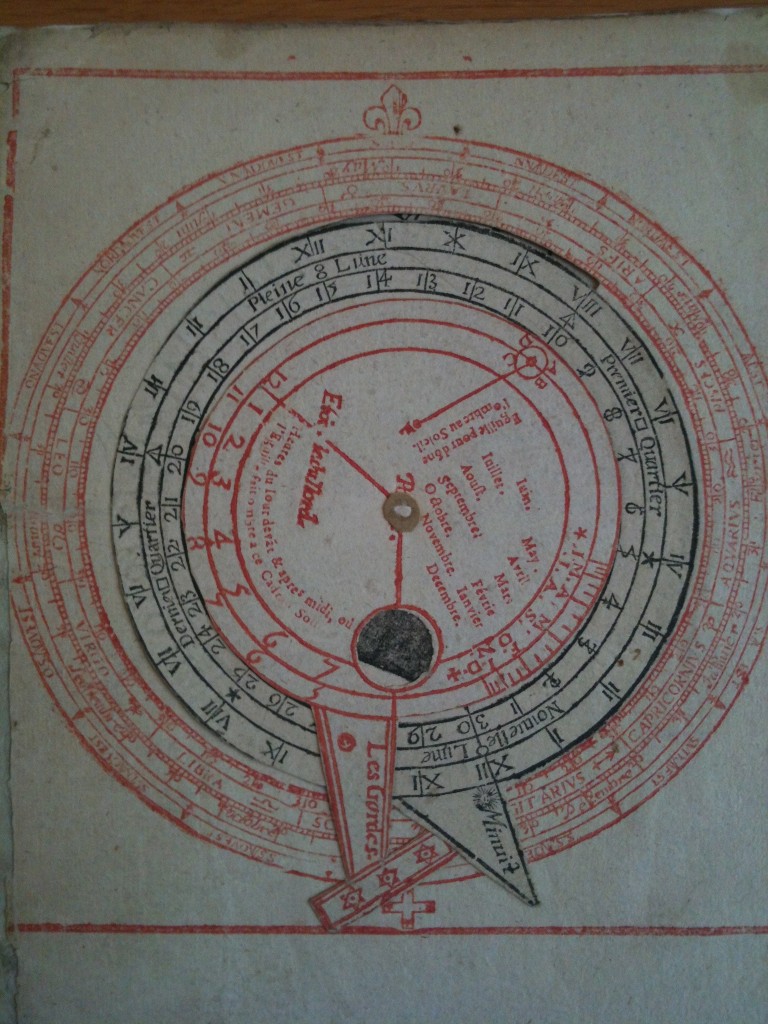

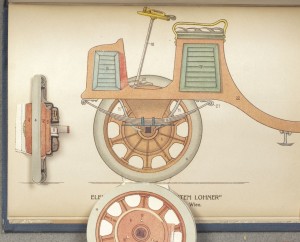

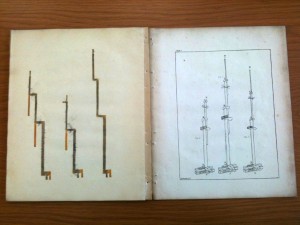

Most of these innovations come together in the work of Erhard Ratdolt, the Augsburg and Venetian printer already mentioned. He was an early adapter: he used a title-page, printed in color and so on. I especially mention the way he placed woodcut illustrations in the margins in one of the most beautiful and well-structured books ever published: his first edition of Euclid that dates from 1482.

Why did changes that were clearly great innovations not find their way immediately and sometime took ages to get accepted. Why did not all printers started to use woodcut initials right after they were invented – why did it take almost a century for such a simple but effective innovation to be generally accepted?

I have a few assertions that may play a role in the discussion of the digital age.

The first one goes like this: what we see as typographical innovation is often a ressurection of something older. Most typographical inventions of the 15th century are in fact reinventions.

My second obervation is that almost all real innovations come from outsiders. The power of tradition is very strong, especially in the field of printing and publishing were innovation is stultyfied by the conservatism of the trade and the consumers.

What does this mean for the future of publishing and more specifically for the future of design? I love the term Information Architecture as it covers perfectly what modern design is really about.

It will be clear that the internet and searchmachines have changed the way we look at information and how we use it. Will we need footnotes when all books have been digitized? I can imagine a searchmachine that analyzes texts in depth: a researchmachine. Now information is anchored to a page but digitized it can have any form – especially as we do not need to refer to a given page any more.

On the other hand the way we organize and read texts will not change. Writing and reading is about rhetorics and expectations and these are deep undercurrents that were probably hotwired into the human brain long before we were able to notice them.

Digital information will always be expressed in books and these books will be more beautiful and better made. More people than ever before are active as designers, of typefaces and of books. They are counted in tens of thousands where there used to be hundreds. Of course beauty and taste have nothing to do with numbers. But more practitioners create more choices for a public that has become more critical in its appraisal.

I think that a few years from now there will be less books than there are now, but they will be better edited, better designed and better printed. Part, perhaps even the greater part, of the mass market will go digital. This will make books less interesting to the kind of publisher or bookseller that now fill the great chains of bookstores with endless and depressing repetitions of soulless and bad designed books. The independent bookseller will rise again and so will the independent publisher. I think that this is the future, an interesting and humane future and certainly our future as bookhistorians.

paul dijstelberge Amsterdam – Netherlands