Today the “Unbound” symposium begins! As part of the registration process, we asked participants: “What questions do you have about the future of the book?” The responses follow ~ please add your questions in the comments!

What will be the future bodies of books?

What’s more perishable, a printed book on archival paper or a Kindle e-book?

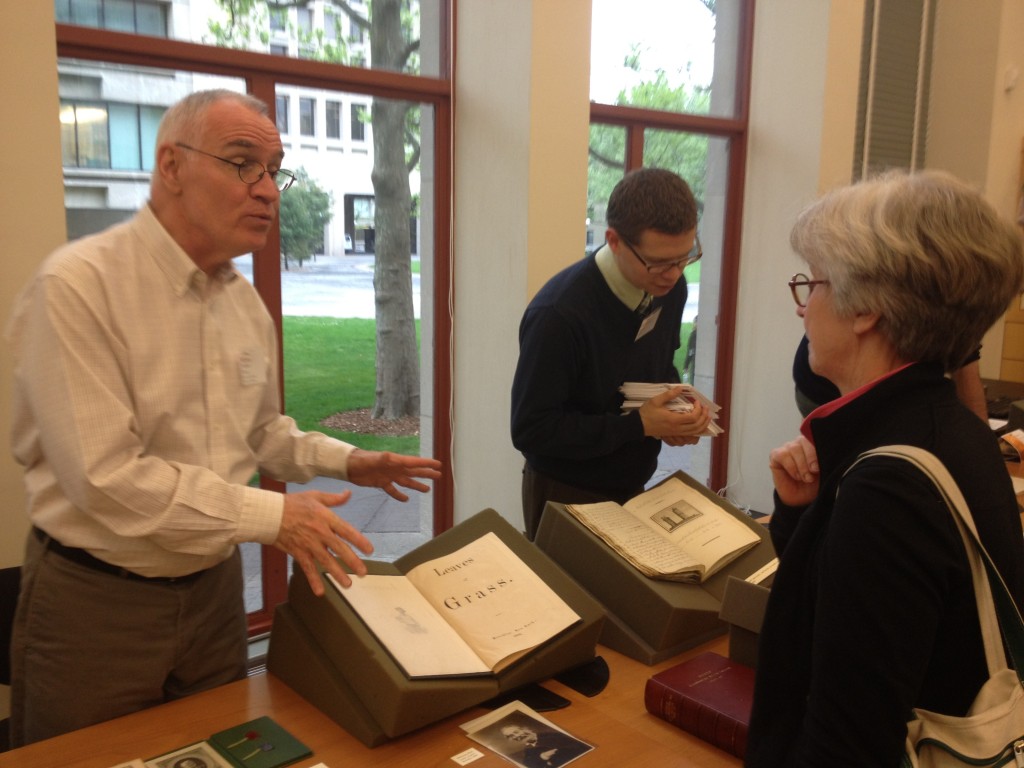

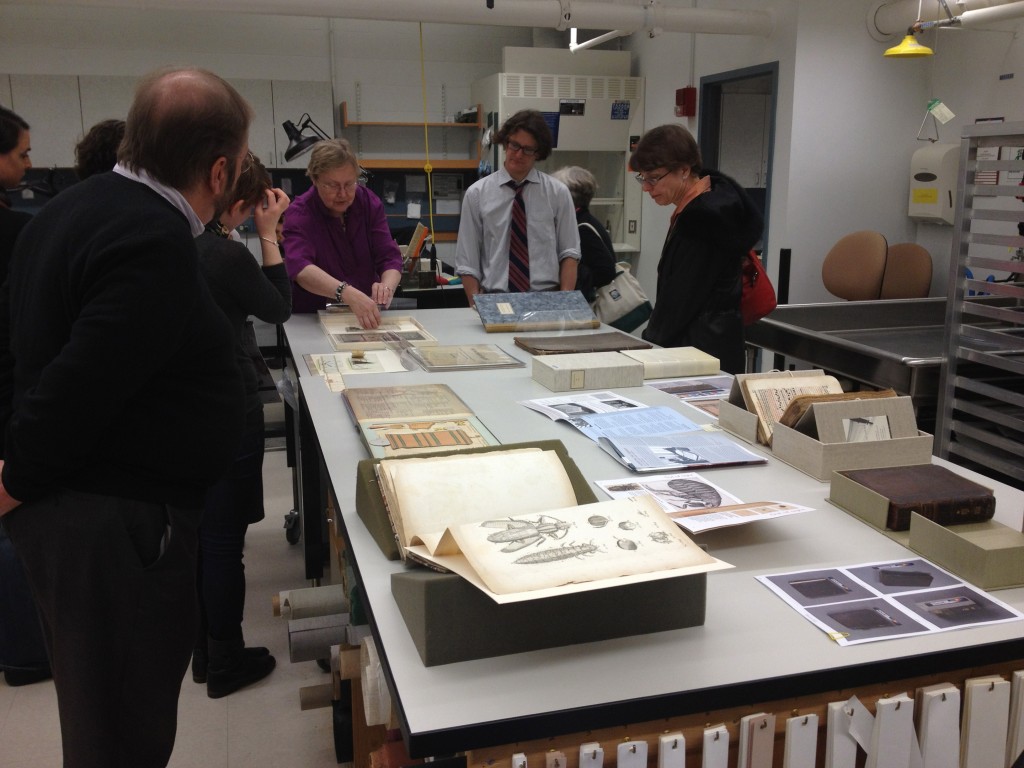

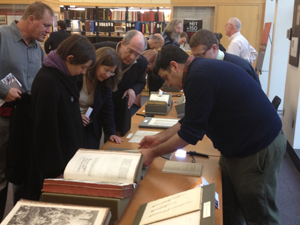

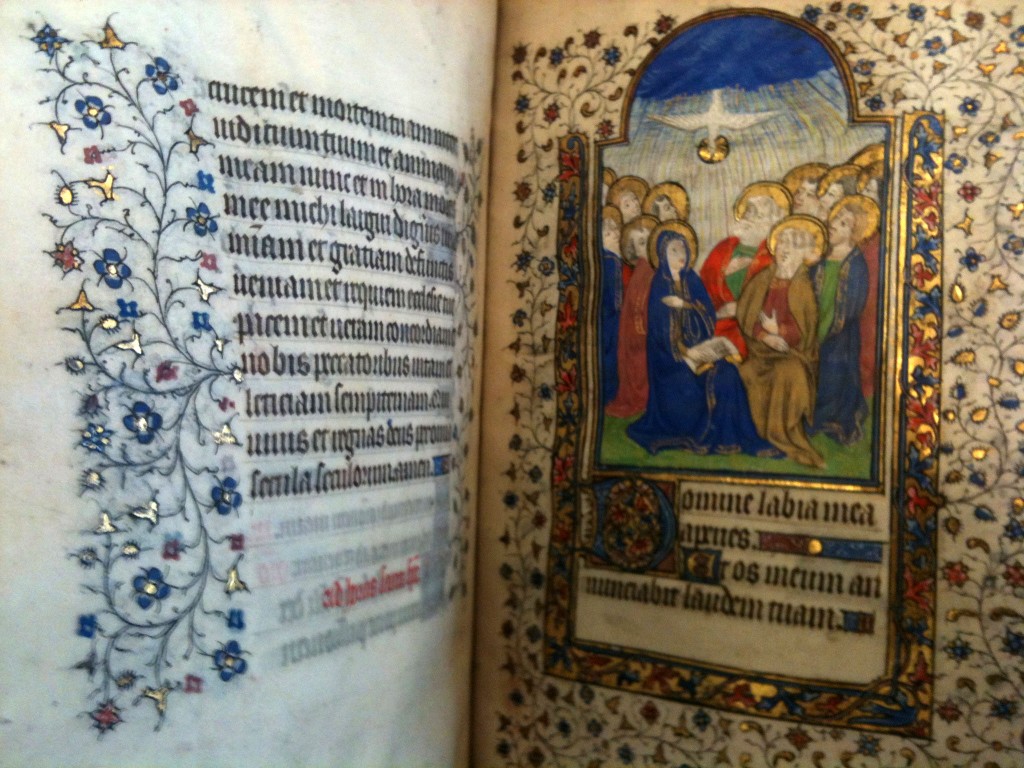

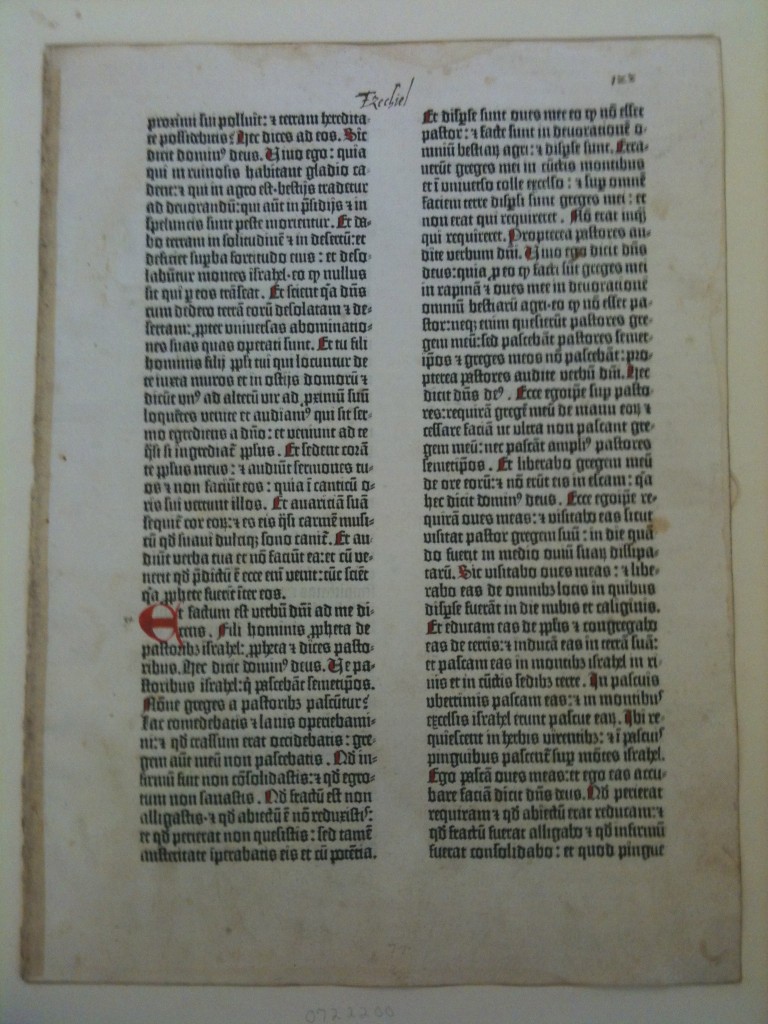

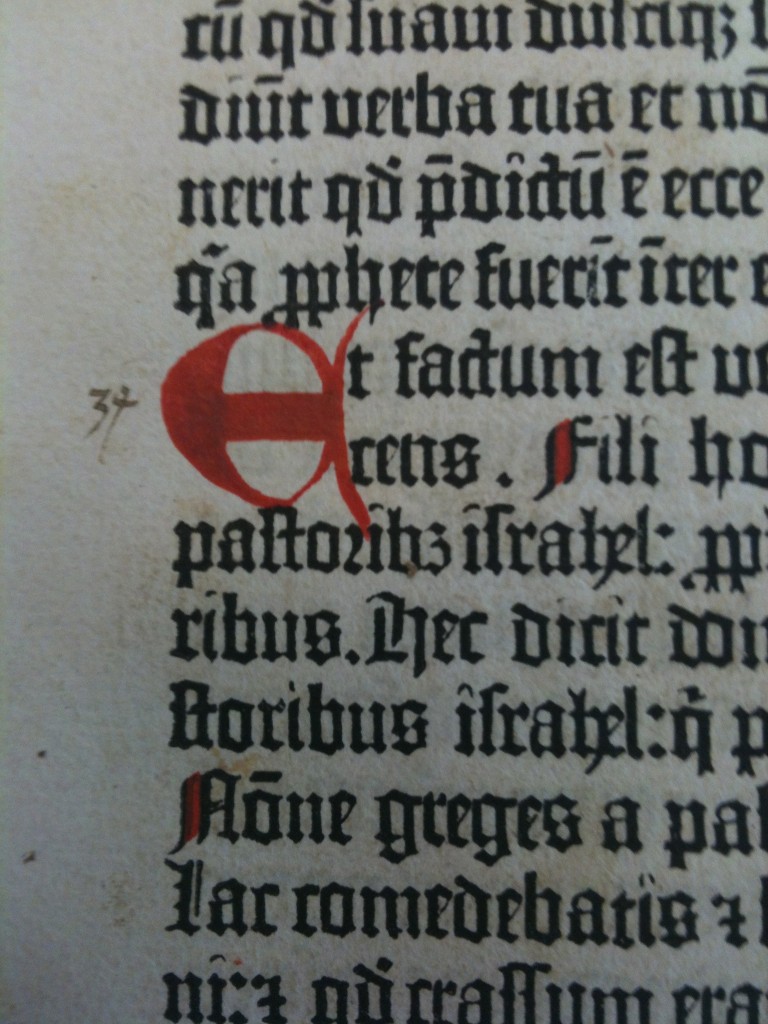

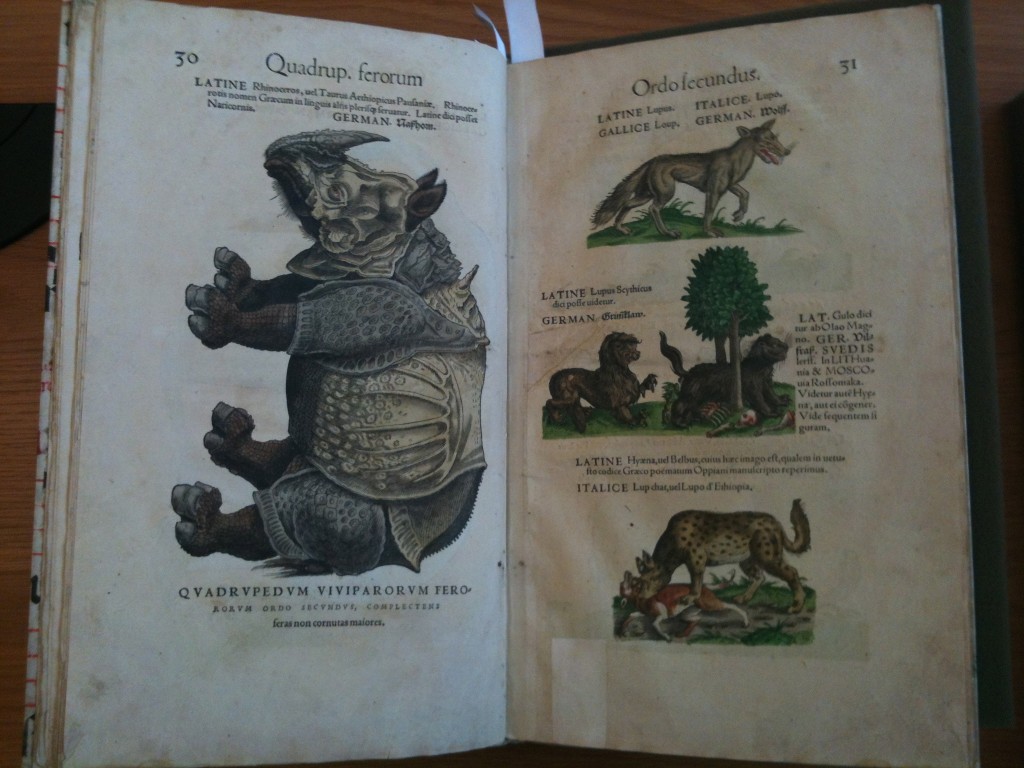

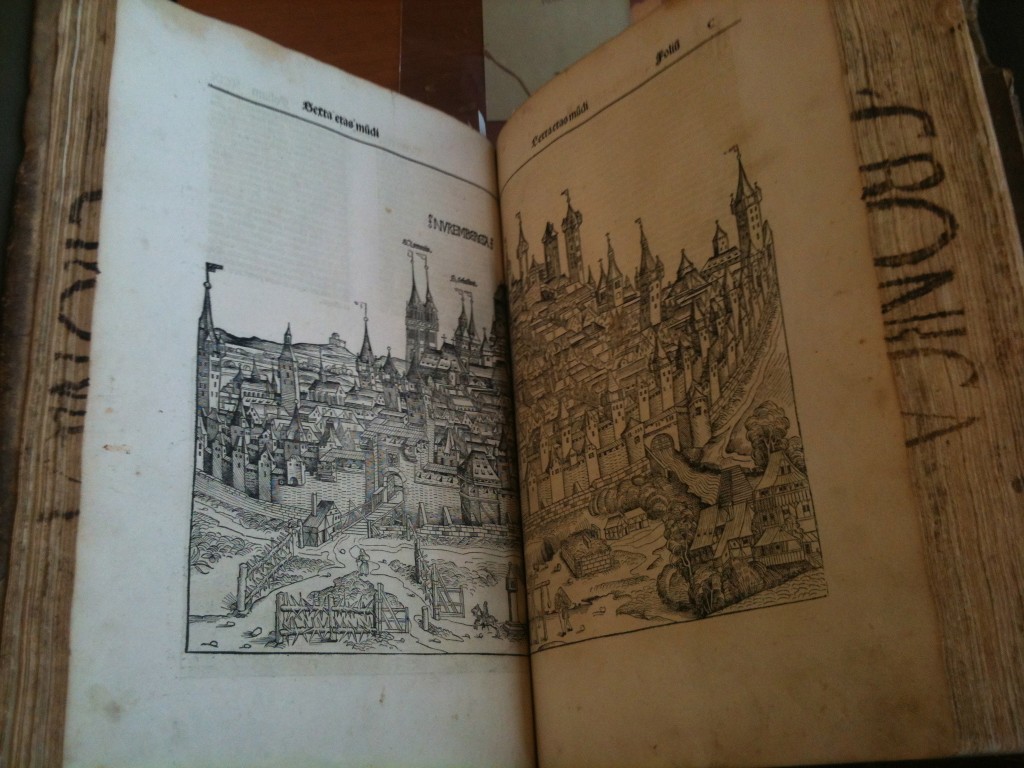

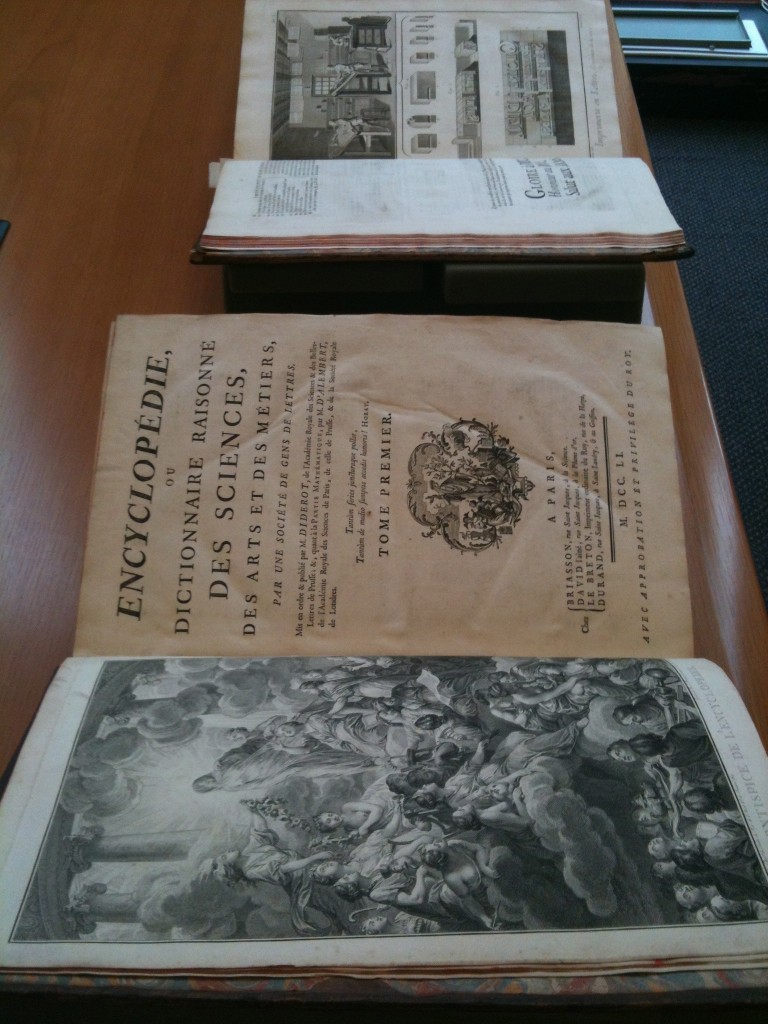

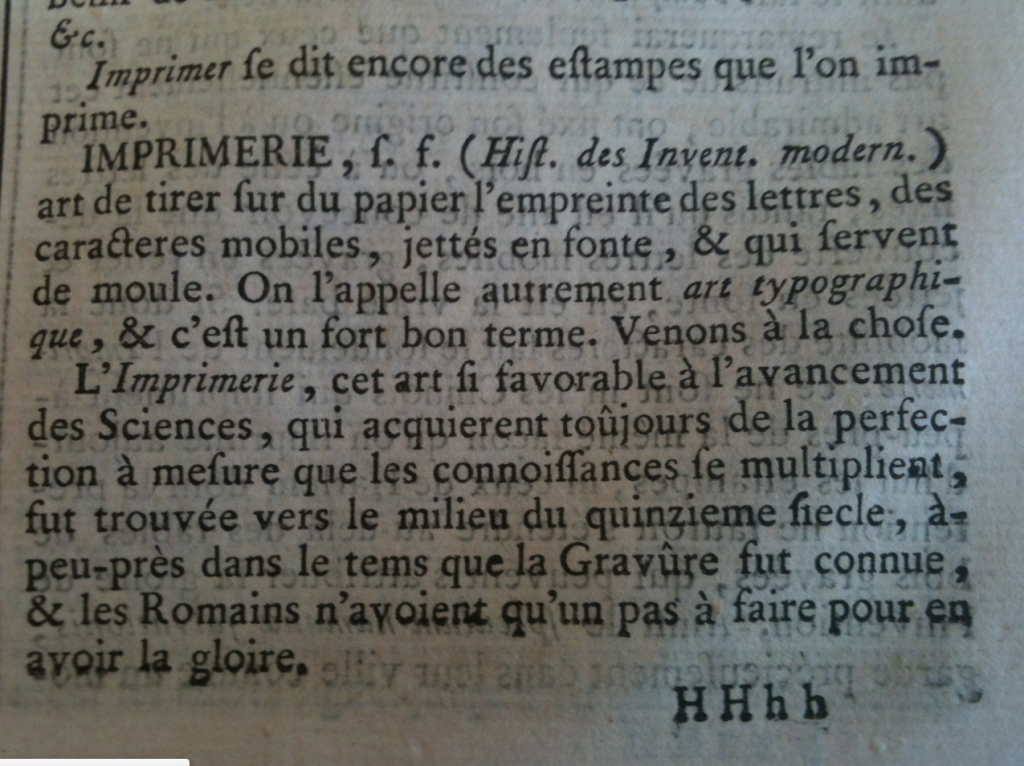

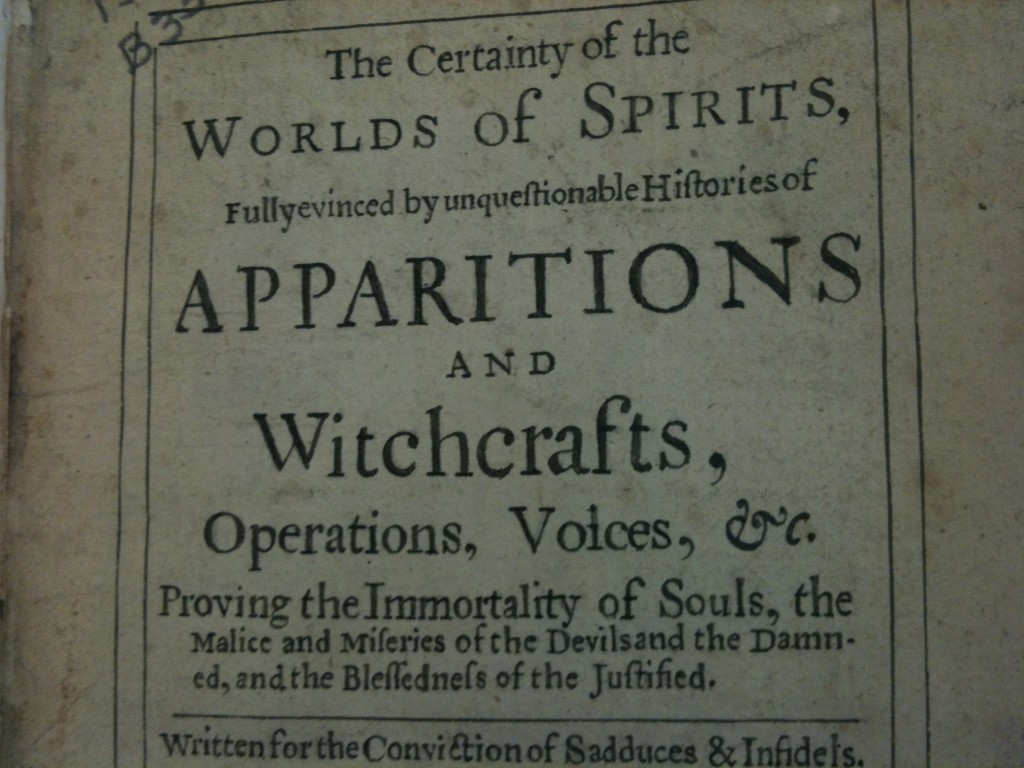

What about access to special collections and rare books, given digitization?

Is the contemporary book form eternal?

Must poetry adapt to preserve its autonomy when read from a device with a screen?

What happens to publishers?

How will digitization effect art libraries/art research?

What changes will new publishing technologies bring to traditional modes of academic legitimacy / tenure / peer review, etc.?

What about access in many forms — open access enabled through digitization, accessibility of e-readers and e-texts to people with disabilities, making archival collections accessible to readers w/sight impairments?

In what ways can we move beyond the tired “death of the book” discussions and focus on the birth of something new? What are the possibilities?

Does the codex book revert to luxury item?

What about new technology and both the challenges and opportunities of that technology?

What is the future of the book as tangible object?

What about digital reading finances?

What is in the future of book discovery, especially in a world with fewer and fewer bookstores?

What are the economic implications behind the future of e-books?

What is the role of the publisher?

What is the role of intermediaries, the access, the collaboration?

How many futures are there?

What about the cultures/communities in which books and other means of info exchange derive meaning/significance, when I am in “the” book as such?

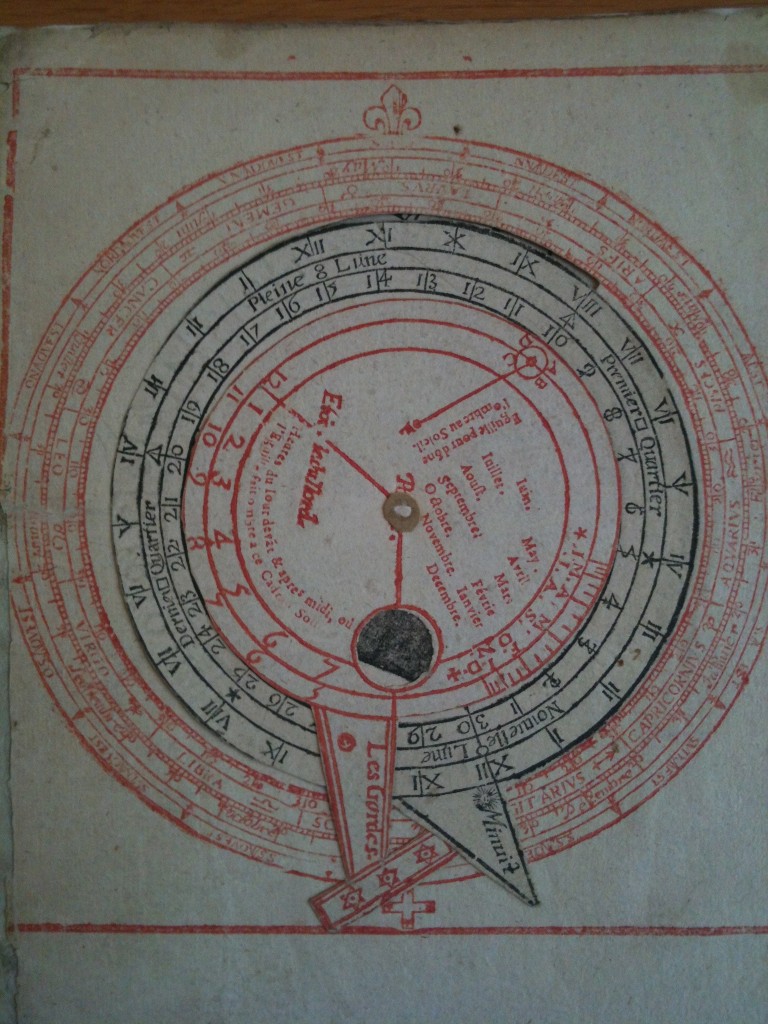

What about telegraphic code dictionaries, books as means to ends?

How do books as physical artifacts anchor truth in a virtual world?

How will traditional publishers embrace emerging technologies and expand their view of the definition of a book?

What new creative forms are made possible by ebooks?

What differences arise in how we read or view digital versus print material, especially in regards to attention and linearity (or non-linearity) and how those differences in form might effect thought processes?

How do we learn and be inspired by the book?

How will the evolving format of the book change the way people read?

Have we learned/are we learning anything about actual differences in the reading experience depending on format (print vs. digital)? (Retention; learning outcomes; aesthetic/emotional response, etc.)

Where are the convergences?

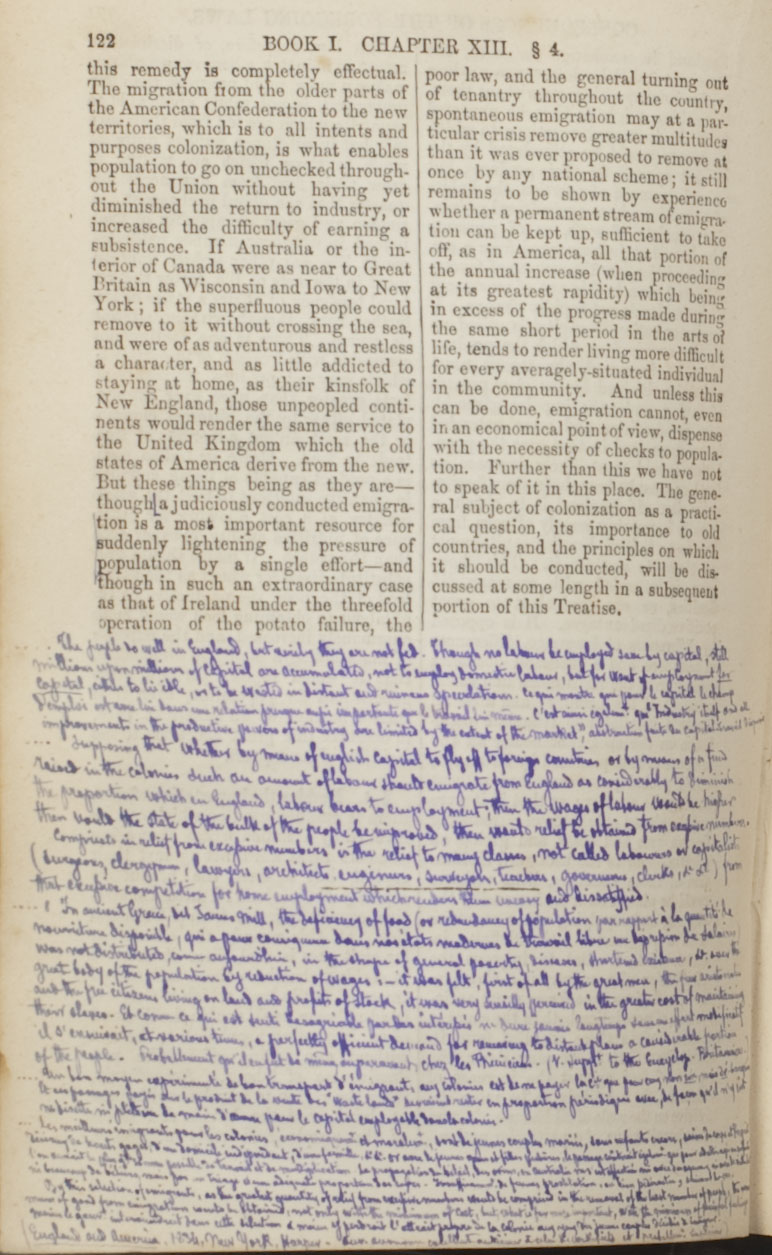

How will we be able to archive and study the progression of a manuscript through pre-publication stages in the electronic age?

How is the future book connected to its past?

What should libraries and librarians be doing to prepare themselves and their institutions for the future?

When will people accept that physical and electronic books must coexist?

How secure/stable/compatable is the archiving of e-books?

How will physical and digital components of books complement each other?

How will various forms of digital books – especially those with dynamic/link elements – be archived and cataloged?

Who pays for e-lit?

Can print and electronic co-exist?

When will printed books cease to be produced?

How will form change content?

What will be the future for hand bound books?

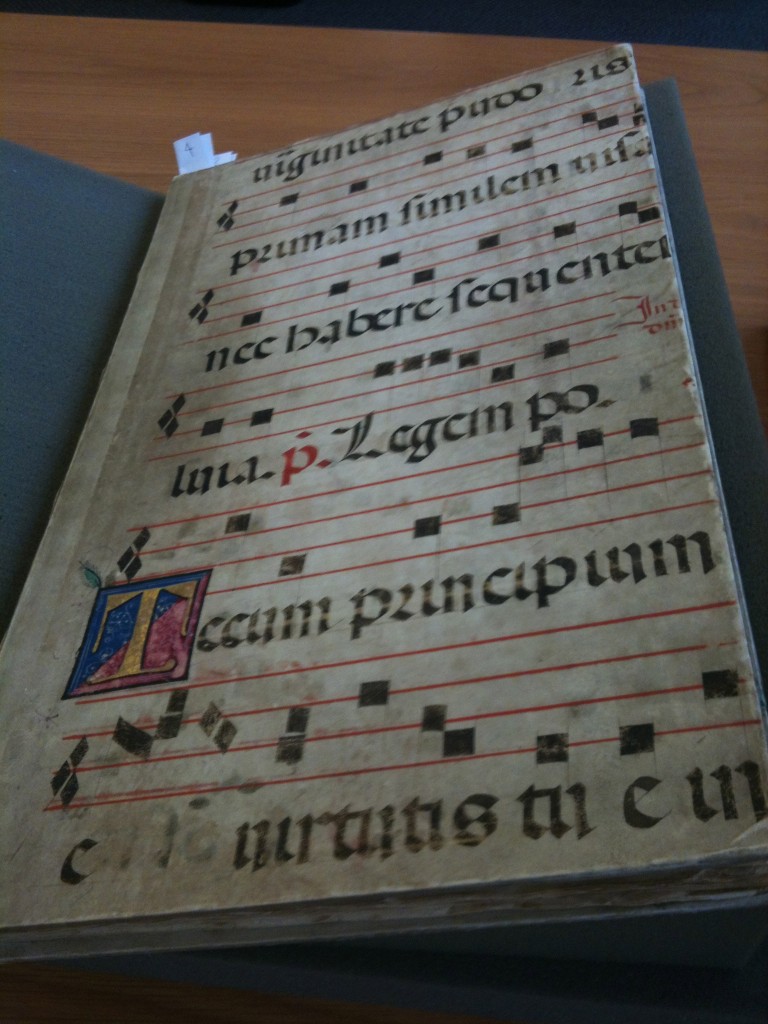

How will old book forms be valued, and their particular haptic values be viewed?

How can we reenergize interest in the book as a physical object? How can brick-and-mortar bookstores survive?

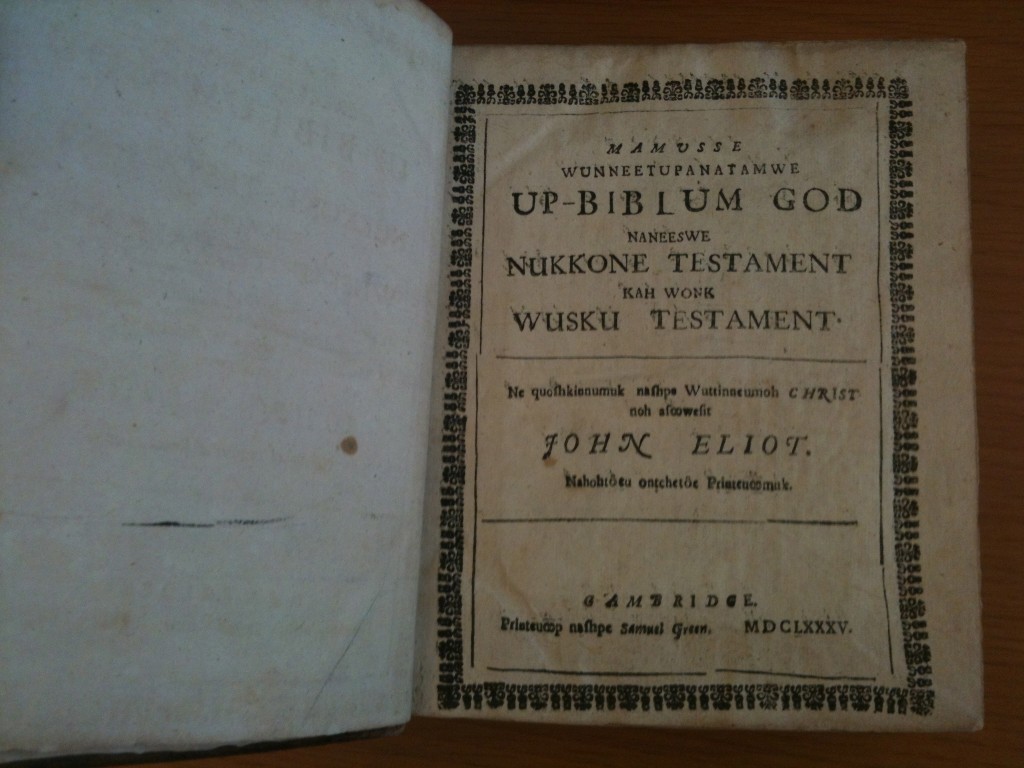

What can we learn about the books of the past to shape the books of the future? Is book the right word to talk about the “book” of the future? Who will have access to the books of the future? What happens to reading & writing in the book’s future?

Is it right around the corner or a long way off? How will we know? How much paper will it involve? What is a book, anyway?

What is meant by book?

What do we want academic publishing to be?

How will e-books achieve a more haptic or interactive aesthetic? It seems like several qualities of the physical book simply can’t be reproduced digitally.

Has the definition of what a book is already changed?

What continuities will we see with the book’s pasts?

What about e-book vs. traditional methods?

Will future technologies such as thin bendable displays with integrated computer/communications components allow a blending of print/electronic books so that a print text can also link to other resources via computer/communications strips embedded in the book — enabling the contents of the book to be updated with new information and links to other information?

With our attention spans getting shorter and shorter with every generation, what kind of future do books have? What does media — social and otherwise — mean for the future of books as objects?

How are authors responding creatively to the new possibilities of publishing in a post-artifact world?

How the publishing industry will have to compromise and adapt in the light of new technologies, and how this will affect readership?

What else can be a book?

Will books become more or less precious as we move toward the future?

Will printed books and bookstores survive the ebook movement?

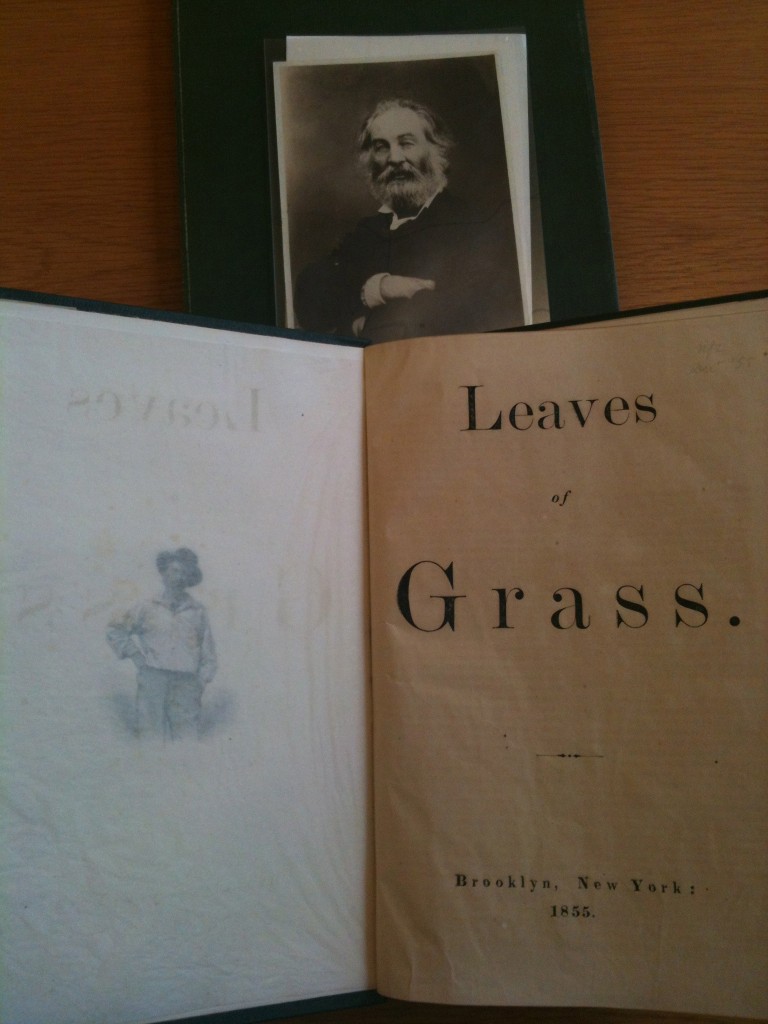

For rare book dealers, what changing practices will arise in collecting, and new theories of the collectible? Maybe it’s time to rethink what’s “first.”

Are e-books here to stay?

How will digital technologies affect the costs of textbooks? Will the cost of textbooks become less of a contentious issue as they migrate into digital formats?

As companies like Amazon and Apple move into publishing, what are the implications, both in terms of what/who they publish and how we gain access to those titles?

When will we have great reader technology?

How will e-books impact collection development in academic libraries?

How will it impact the discovery and dissemination of knowledge and research?

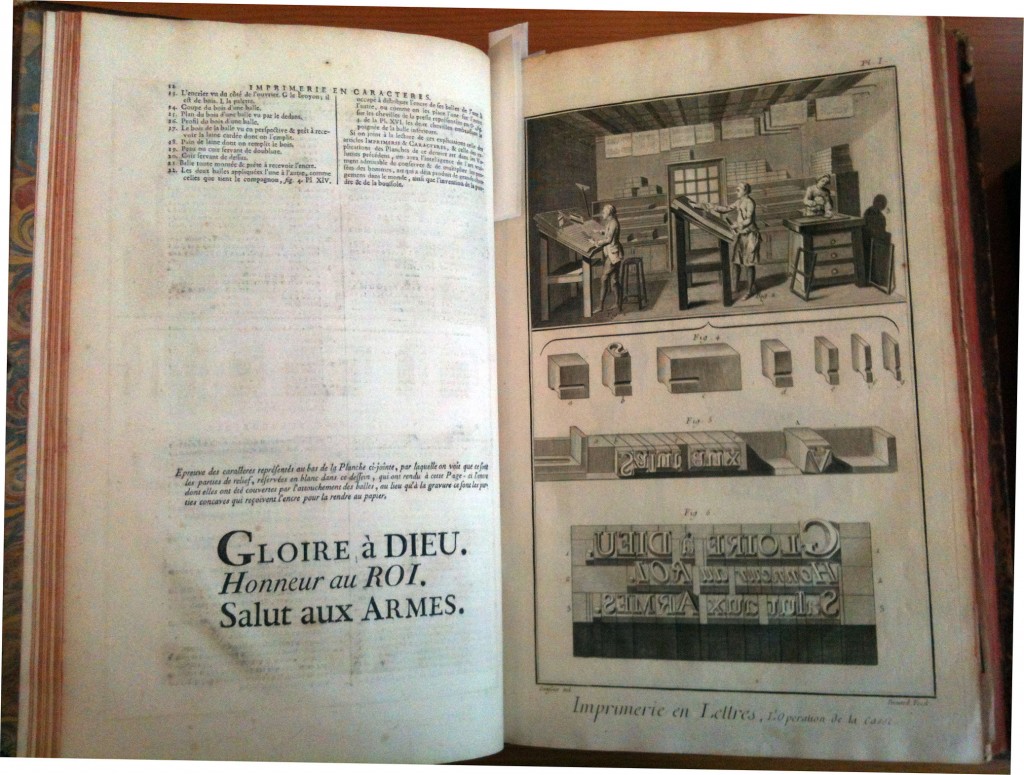

The book and linear thinking; the book as object; having and holding vs. access; labor process and book production?

What about digital curriculum as well as the future of the publishing industry?

Is the future of the book something we should be so concerned with? Evolution is the trip itself, not the planning for it. It will happen and maybe the anticipation is fun but it will be more like a roller coaster ride, we just hang on and enjoy the trills.

I have been dismayed by the amount of whining that I hear about the advent of digital media and hope to hear some intelligent people considering the ways in which new technologies will solve some problems of information dissemination that the book was not suited for — also would like to discuss the place of the physical book in a digital age, how the Espresso machine can work in tandem with digital publication, how literary production might develop, etc and so on? So long as there is no whining about how print is the only medium in which we should trade.

What forms will books take as time passes?

Ten year ago, folks at MIT were working on digital ink and now we have the Kindle. When and how we see the melding of digital tech with the tactile qualities of paper?

Will the book as we know it disappear forever?

What kinds of scholarship are fostered or constrained by printed books and by electronic books?

Can print and online books survive together and compliment each other?

How long will books be published?

Will there be books as we know them in the future?

What are the changing readerly practices, and how do they impact the relationship and roles of the author and the reader? How can/will book history inform the form and circulation of the the future of the book?

What about digital preservation solutions for e-books and related media?

Is there an “other side” to this watershed?

Can technology fully replace the experience of interacting with print material? What qualities would be required in a technology for that to happen? Will publishers really ever come to a place where they are comfortable publishing in only digital form and in a common format that can be used across platforms?

How quickly are people shifting from books to e-ink? How are university librarians thinking about the next 10 years?

How will e-books change the nature of teaching, learning and research? How will the use of multimedia can enhance the experience of the print book?

What is the right pricing method for the future forms of books and magazines (printed, iPad/iphone/kindle/nook versions)?

How will digital possibilities change the ways that book artists make books?

What will be the venues for innovative print fiction in a market-driven climate in which an ever-diminishing number of readers purchases books? How do libraries complicate the issue if they are relying more and more on electronic resources? How does the Internet affect the trajectory of literary history?

Why the pessimism over books as they have largely existed for centuries?—deathbed or immanent change in the description nudges out thinking of the book (which is also more plural than the description suggests…) as not needing to change (or us…).

How are we going to preserve and share books in the future if print gives way to digital?

Where are we headed? Are books to become a dusty collectible, or is print necessary to validate the efforts of knowledge seekers and creators?

Will e-books replace print books eventually?

What is the future of the e-book?

Will there be free repositories of books in whatever format (physical, digital, etc.) preserved for posterity? Who will be the guardians of our history and our culture, the custodians of civilization, in the future? Will it be “Free To All?”

How will authors reach readers and how will readers find books in the evolving landscape of publishing?

Do changes in the material form of the book affect learning? Who will preserve digital culture? Who will ensure our existing works of culture are moved into the digital age? If books are digital how do we ensure literacy crosses the digital divide? How does image inform text and vice versa?

The popular media, format, and distribution channels of future books?

Especially interested in ways of facilitating access and exploring digital (and other) interactions with special collections books and mss. in the future?

How will digital texts interact with printed texts? Printed texts for the pleasure of reading, digital texts for research? Will we see an increase of book art and bibliophile editions?

If libraries are about classification, storage, and access to content, and that content becomes online, how can and should academic, research & public library spaces change?

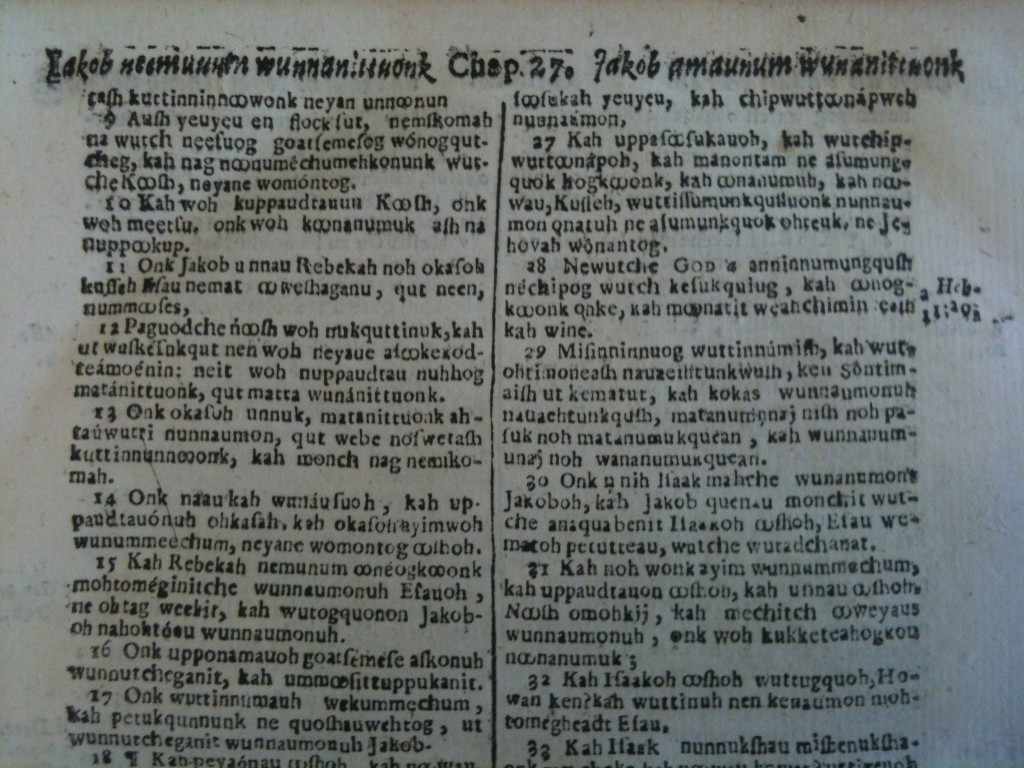

How will the shift to “modern” forms of the book affect our relationship with more traditional textual forms?

Confirm interdependence of print and screen?

What about paper? When will e-books become independent from a power source?

What will happen to indexing and other aspects of book production?

What media types that wouldn’t resemble books enough as to still be called books might displace the book? I mean, virtual books are still books; for instance they all still have pages.

I don’t have questions but am interested in hearing questions.

What is the future of books on paper?

Will it survive?

When considering the future of the book, where do bookbinders fare?

How can e-books and digital media be extended to incorporate the tactile richness of handmade paper and letterpress printing?

Many questions. Here’s one: Physical books began as precious objects, but the great majority of them eventually became very common. But is it possible or even likely that the physical book is destined to become a species of precious object once again?

Where and how will the kinds of sustained narrative development found in long fictions and complex scholarly thought be preserved/reinvented appropriately?

Will the proliferation of e-books have the opposite effect of regenerating interest in (paper-based) fine press books?

When will paper books disappear for good?

How will education in schools be changed by the digital book?

What about the future of print publications?

What are others imagining future forms of the book to be whether hard copy, electronic, or other?

Where does the line exist between practicality and fine art in the future of the book?

Will access to knowledge actually be limited rather than opened if we go completely over to electronic books rather than print ones? What is the future of the library?

What does the library of the future look like?

How will we produce humanities content in digital form? How will we move humanists into digital publishing?

iBooks/e-books are a sustaining innovation over the traditional print. What will be the disruptive innovation?

Currently using four different forms of “books” in daily life. How many forms will we use simultaneously in the future?

Will devices dictate the future of the book? That is, will what we read on be the most important component (rather than the reader, the writer, etc.) in determining the future of the book? What better devices are on the way?

How new “books” may be experienced; image/text relationships, etc.?

What does the rhetoric of the “digital revolution” seek to obscure about the long-standing tradition of the book?

Do we still value the relatively stable form of knowledge the book represents — or is it the conversation, the process, and the proposition that we care about today?

Can we think of the future of the BOOKS, as in the many forms books can take, as they have in the past? (General) What are margins, and how can we use them creatively in the books of the future? (Particular)

What are the implications of robotic writing for the future of poetry?

Will Amazon eat all players?

What about conversion of textbooks to electronic format?

In what ways are the e-book world collaborating with the gaming and artists’ books world? It seems like a trillion dollar future.

Why are audiobooks seldom included in the book’s future?

What lies behind our era of ‘unbound’ness? Why do our stories need new technological mediums to be told?

What are the implications for Catalogers? Are readers less interested in actual books?

Electronic publication has broadened writer’s access to both the means of production and dissemination for their texts. Should publishers, editors, agents, and critics others continue to play their traditional roles as cultural curators (and gatekeepers)?

Will the book remain an essentially ad-free medium?

How does the print industry regain momentum?

Why didn’t the book die out long ago?

How to best meld the print book with the eBook for preservation of the scholarly historical record? How to sustain the use of the print book both for its intellectual content and for its physical form as an historical or art object?

Where is the book headed?

How might history and tradition relate to emerging digital forms?

What technological and legal changes need to occur before the on-screen “page” captures images (art and text) with greater typographical and visual representation?

Will scholars who have long prospered using print material be forced to use visually-challenging, tactile-wanting and aesthetically-boring e-books??

Is publishing turning to transmedia to counteract the losses in print fiction?

The codex — what we think of as the “book” today — seems likely to endure for centuries to come as a means of storing and transmitting information. What I’m interested in as an author is what story-forms are enabled by electronic media — I’ll point to Christine Love’s “don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story” as a story which cannot be told as effectively in any form but the form she gave it. So, what aren’t we doing yet that we could be? What stories can we tell electronically that we can’t tell otherwise?

Where do you think it is going? Do you think people will ever want to give up the physicality of the book as an object? Isn’t there room for other avenues of bookmaking, without threatening the book?

Which future?

How can books become multi-modal, combining sensorial and abstract forms of representation?

How might collaboration in authoring/bookmaking come to greater prominence considering the ways in which book arts/artist’s books expand the notion of what a book is, and the ways in which social media encourages communication and exchange, and obliterates geographic and temporal barriers to co-creation?

What about new formats for storytelling?

How responsive will the ‘Future of the Book’ be compared to the ‘Past of the Book’, which has been admittedly rich and successful?

What short-term and long-term business models, particularly models involving sharing e-books and DRM-free (or DRM-easy) e-books are on the horizon?

How will we assure that books don’t just “disappear” (get deleted from e-readers)?

Will paper books become vintage/collectors/luxury items, like LPs? Will e-reader technology keep changing as quickly as other forms of media (VHS to DVD to Blueray, record to tape to CD to mp3…)? How will that change how we read?

What about new reading practices related to new material forms?

What will the book of the future look like?

How do future books relate to the future of museums + archives?

When will libraries become obsolete?

What is it – the future?

How do we imagine the book, as an object or as a site where inquiry happens? How does prioritizing one over the other change how we make new books and preserve or reinvent the idea of the book?

Will sustained argument and narrative matter much in the future?

Will unique artists books be more relevant?

Ah, the many varieties of e-books….

Books are the traditional venue for contributing ideas to the public forum. Digital media favors shorter communications such as blogs and tweets. For expansive, detailed content, do physical books have a future as a preferred format?

I’ve heard that bookstores in Germany are thriving. What are they doing that we are not?

To what extent should readers/participants be able to add to or revise digital content?

What about the intersection of the future of books and higher education – and how it will further change within the next decade?

What is the relationship between communally and informally generated content and concepts of intellectual ownership?

How is narrative changing (in text and image) and who is in charge?

What is the best working definition of the word “book” as we move forward?

As a printer/publisher part of a virtual artists collective, how can I reconcile beautiful books (and fine craft) with e-books? Without losing sight of the history of books, or encouraging the attitude I’ve seen as a bookseller that the object-book is merely trash.

How will bookstores and bookselling change as the digital revolution proceeds?

How will changes in book technology be reflected in rare books libraries & special collections?

How will new forms of books/media change our way of perceiving literature/content?

Who will give digital books their form? Artists, designers, and craftsmen—or programmers and corporations?

What initiatives are being developed to protect the privacy of readers?

What are we losing about the experience of reading when we move from physical to digital artifacts? What about apps, robots, toys, physical devices that augment the reading experience?

What about the impact of e-books on the definition and future of the book as an artifact?

Is an enhanced e-book (embedded video, audio, etc.) still a book or something different? Will the reader ever come to expect that type of additional content as part of the reading experience?

How soon will ebooks be the majority of the published books?

In view of the increasing ease of self-publishing, what is in the future for traditional publishers?

What is the relationship with book conservation?

Are we romantic enough as a race to hold on to the physical paper book out of pure nostalgia?

Will the hand-made book increase in popularity? How do artists disseminate their limited editions?

How will that change the kind of book or story that we want to read?

To what extent will books become interactive as print books increasingly give way to eBooks that allow for enhanced audio and visual components? Is an interactive book a positive development?

Curious to thoughts re the birth of a renaissance of fine/craft printing (ala Vale, Dove, Kelmscott, etc). Will the ‘death’ of the ubiquitous (and poorly designed/printed) book reopen the doors for the well-designed ‘object’ of the book…?

Are we currently suffering from a signal to noise problem in artist books?

How can e-books create innovative ways to give form to imaginary realms via audiovisual modes of storytelling?

How will/is the change in format of books/print journalism affect how we learn?

How will the DOJ antitrust suit affect the future of e-book pricing? What’s a practical and effective solution to digital piracy?How will libraries circulate ebooks, and will publishers start to work with them to provide access to all their titles?

How with publishing and distribution models change as self-publishing and e-first publishing gain legitimacy? How will the traditional role of publishers change in this new world? Will “book” mean something new?

Will poetry ever transfer to digital technology?

Is print truly dead?

How does the evolution of books affect scholarship and publication trends?

What’s iOS?

What is the future of libraries?

How long will print books survive?

What are ways that traditional publishing models can transition quickly to digital workflows? How can digital workflows be implemented more quickly?

I’m still learning about the history of the book, so I haven’t gotten far enough to think about the future. What about book arts and bookbinding?

What the collaborative and interactive opportunities will be?

How do libraries prepare for a transition from a tradition paper format to another?

When will scrolls return to common usage?

What about curating and providing access to digital objects? What will the future environments of libraries look like? How will the future of the book affect the artifactual value of the physical object? Does the digital book have value other than informational?

How will close reading be enhanced in the e-world?

For how long will print books survive?

How do you explain that if the book format of document has been around for hundreds years that it is not going to be obsolete any time soon?