– guest post by Julia Panko (University of California, Santa Barbara)

In the past several years, the concept of “touch” has become a strategic marketing point for digital devices, from the iPod to the Kindle. But how might “touch” matter as we think about the print book? How might tactility impact the book’s role as an information storage medium and reading platform?

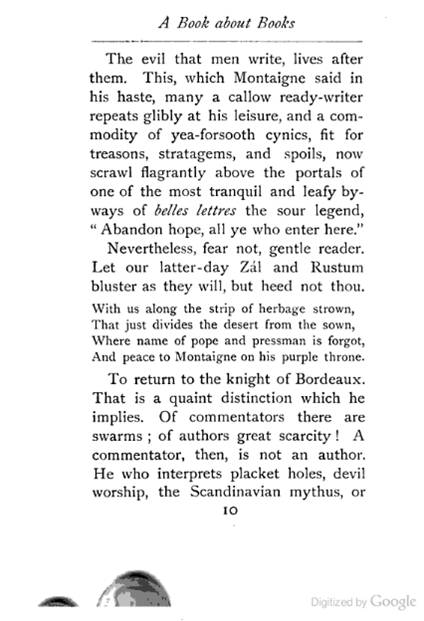

Page scan from Google Books, capturing an image of the scanner’s fingertips touching the page:

Personal archives

When a reader touches a book, she leaves physical traces—fingerprints, crumbs of food, bent pages, pencil markings, etc. We touch digital devices when we read from them, of course, but these surfaces tend to be more resistant than paper to acquiring such traces. The haptic “data” that readers leave in books has forensic value: it can reveal information about a reader’s body, reading habits, emotional attachments, or favorite brand of coffee.

The three-dimensionality of the book also allows it to function as an archival space. A reader might accidentally leave a bookmark or a pressed flower between the pages. Or he might choose to keep significant objects in a book, such as photographs or letters. Print books are storage media in the sense that they contain textual information, but in cases like these, they also become material archives.

Social networks

As books circulate among readers, acquiring annotations or simply traces of wear, they become sites of social exchange. As Virginia Woolf put it, “We like to feel . . . that other hands have been before us, smoothing the leather until the corners are rounded and blunt, turning the pages until they are yellow and dog’s-eared. We like to summon before us the ghosts of those old readers. . .”

Many annotations in books are social in nature. Readers might argue or agree with the author in the margins:

“The frame of mind in which a reader can address a book as though it were another human subject, and present, is one we must all recognize. It can be compared to the more often discussed dramatic illusion, our voluntary and habitual submission to the conventions of the stage. It is not that we are actually hallucinating, believing the actors to be the persons they represent, and us invisibly in their company. Nor does any reader believe the writer of the book to be speaking the words in it, and available for conversation. That fact does not prevent us from cherishing the illusion of intimacy, much as we do in the theater” – H. J. Jackson, Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books

Alternately, we might write an inscription in a book that we plan to gift to a friend or scribble notes in a library book. I have vivid memories of discovering a lively discussion in a library copy of an Agatha Christie mystery years ago: several readers had recorded their speculations about the murderer’s identity at various stages in the story, inspiring later readers to debunk these guesses and offer alternate theories. The book became a tactile record of a community’s interpretive debates.

Aesthetic artifacts

Our awareness of tactility also factors into our appreciation of books as aesthetic objects. When Julian Barnes won the Man Booker Prize in 2011, he spoke of the importance of his book’s design: “Those of you who’ve seen my book—whatever you may think of its contents—will probably agree that it is a beautiful object. And if the physical book, as we’ve come to call it, is to resist the challenge of the e-book, it has to look like something worth buying and worth keeping.”

As we speculate about the future of the book, we must admit that it cannot compete with computers and e-book readers when it comes to sheer storage capacity. The register of touch, however, reminds us that information storage is not the book’s only affordance. Our experience of books as material objects is also meaningful.

Books produce tactile, visual, and even olfactory effects.

The range of sensuous experiences that books provide is perhaps one of the reasons that so many readers describe feeling emotionally attached to—touched by—their books.