To ground the symposium’s future-looking slant on the BOOK, there will be an Open House in MIT’s Institute Archives, Special Collections, and Conservation Lab on Friday morning, May 4th (10:00-11:30 a.m.). The Archives have a fabulous collection not only of science and technology holdings, but also of materials ranging across disciplines and print media. Here are a few highlights that will be on display for visitors to see and handle, akin to a mini-history of the BOOK. To learn more about MIT’s Institute Archives and Special Collections, click here.

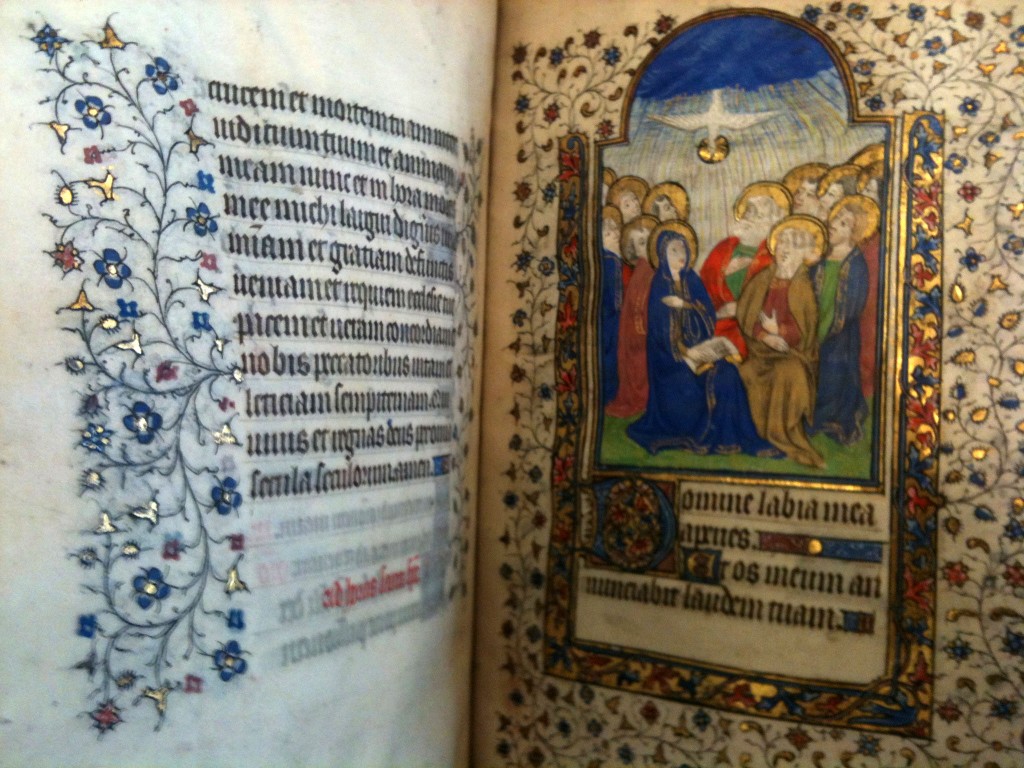

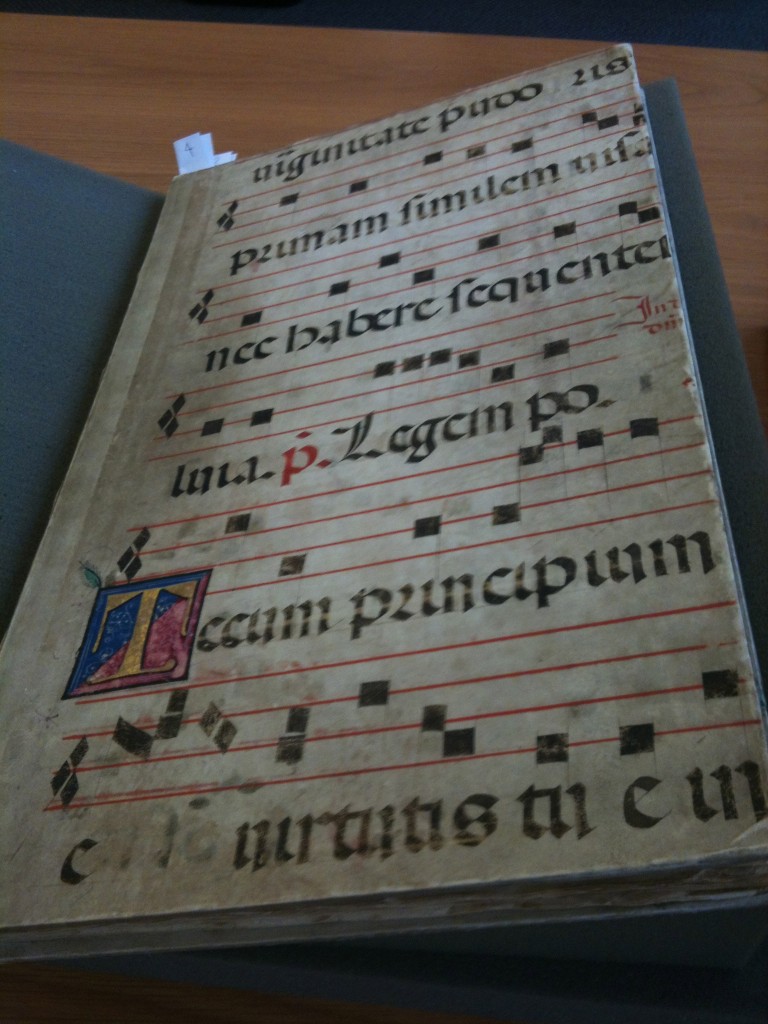

BOOK OF HOURS use of Paris, Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis (France, 15th century) Uncataloged

This is a fine example of a manu-script, or a text “written by hand.” Books of Hours were private devotionals in the Middle Ages. One famous example is the Belles Heures of the Duke of Berry. A colorful anecdote about Anne Boleyn’s Book of Hours recounts how she and Henry VIII used her book as a mode of flirtation! To learn more about Books of Hours, click here.

QUARTO SHEET (folded to make pages of a book)

To learn more about collation, see here.

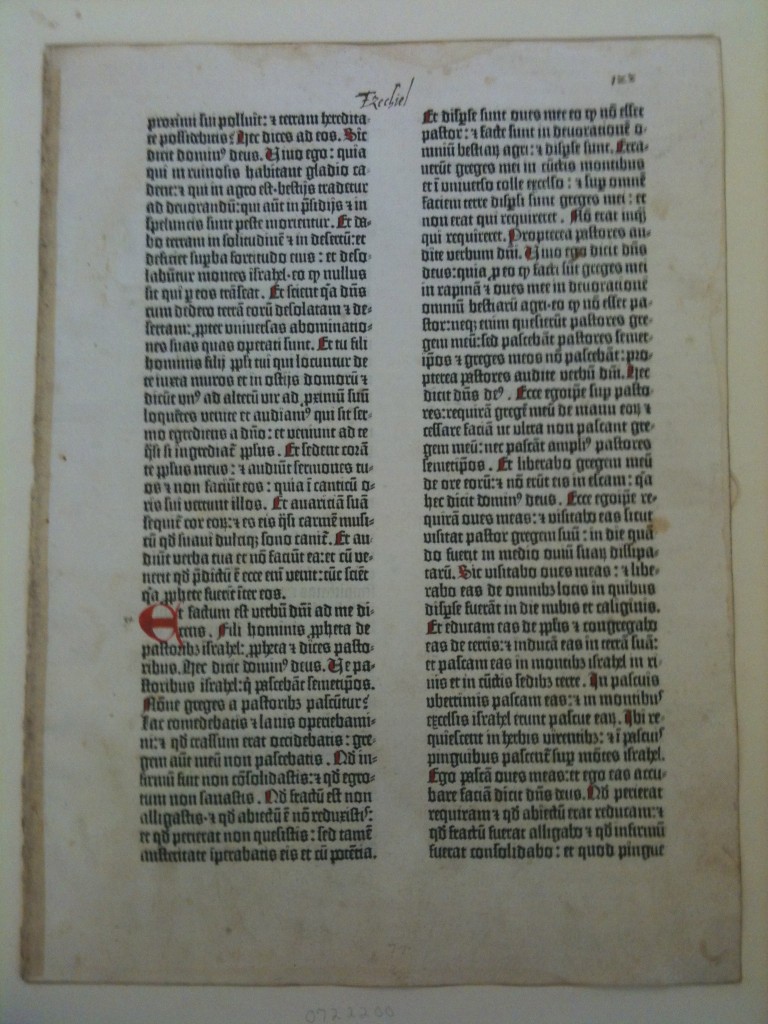

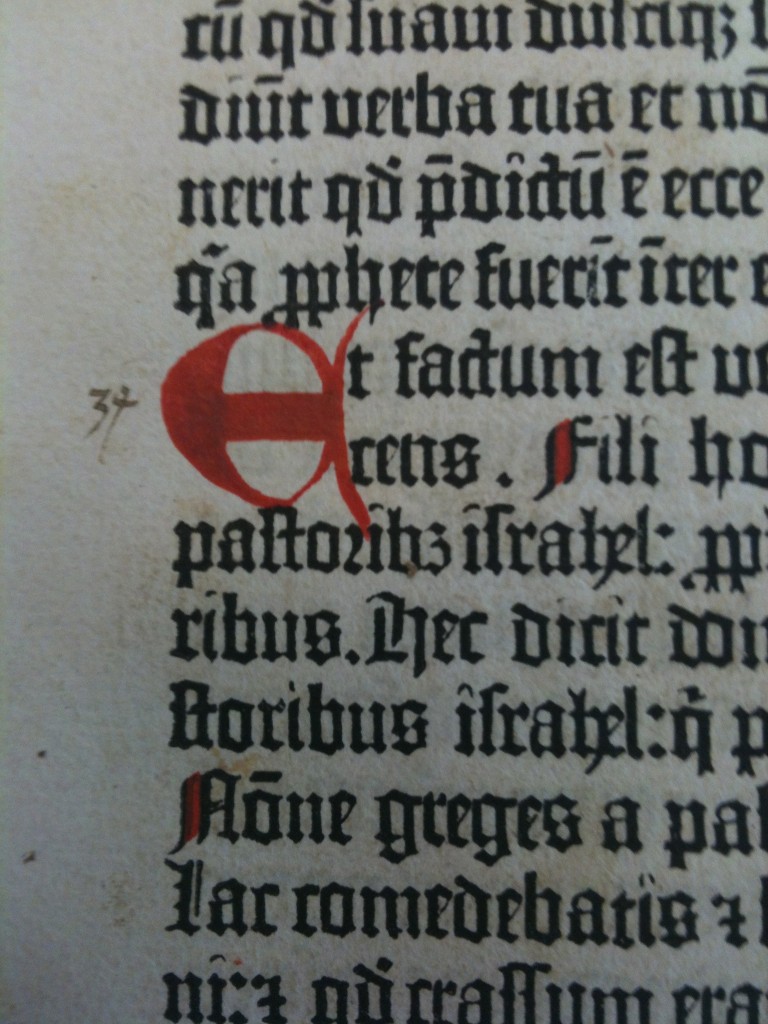

LEAF FROM THE GUTENBERG BIBLE (Mainz, ca. 1454) Uncataloged

When this particular page was discovered in a hut in Germany, it was learned that other Gutenberg leaves were being used to cover local children’s schoolbooks. Compare copies on paper and on vellum here, or check out this “Anatomy of a Page.” When you’re ready to view the next item, try to judge that book by its cover…

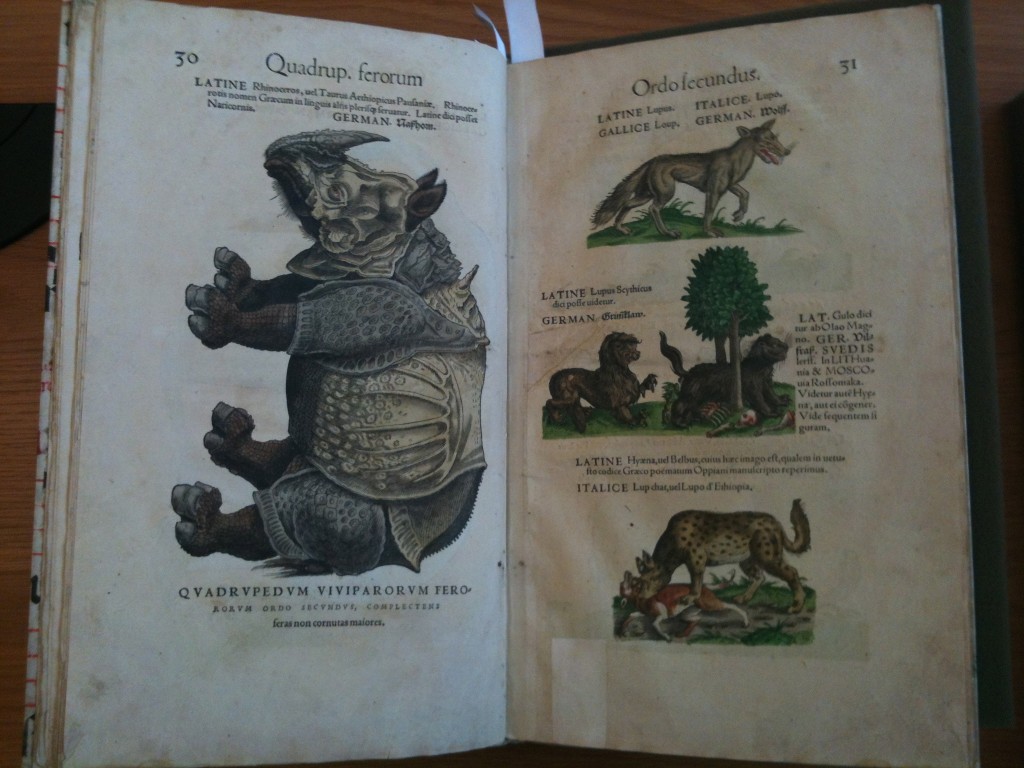

BESTIARY, or Conrad Gessner’s Icones animalium quadrupedum viviparorum et oviparorum (Zurich, 1553) QL41.G391 1553

From its cover, this might be guessed to be a book of music rather than of beasts. But look below to see what lurks inside. The rhinoceros is a copy of Albrecht Dürer’s famed print. In addition to recognizable animals like lions and dogs, the book also contains unicorns and monsters. The book is printed, but the images all are finely hand-colored.

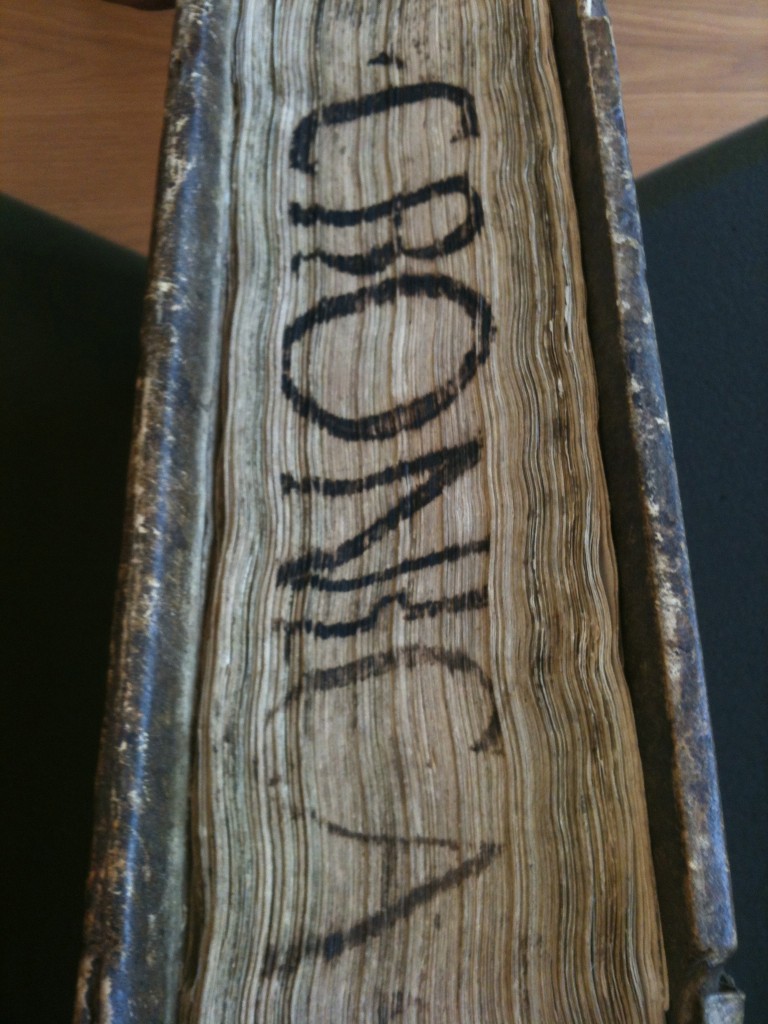

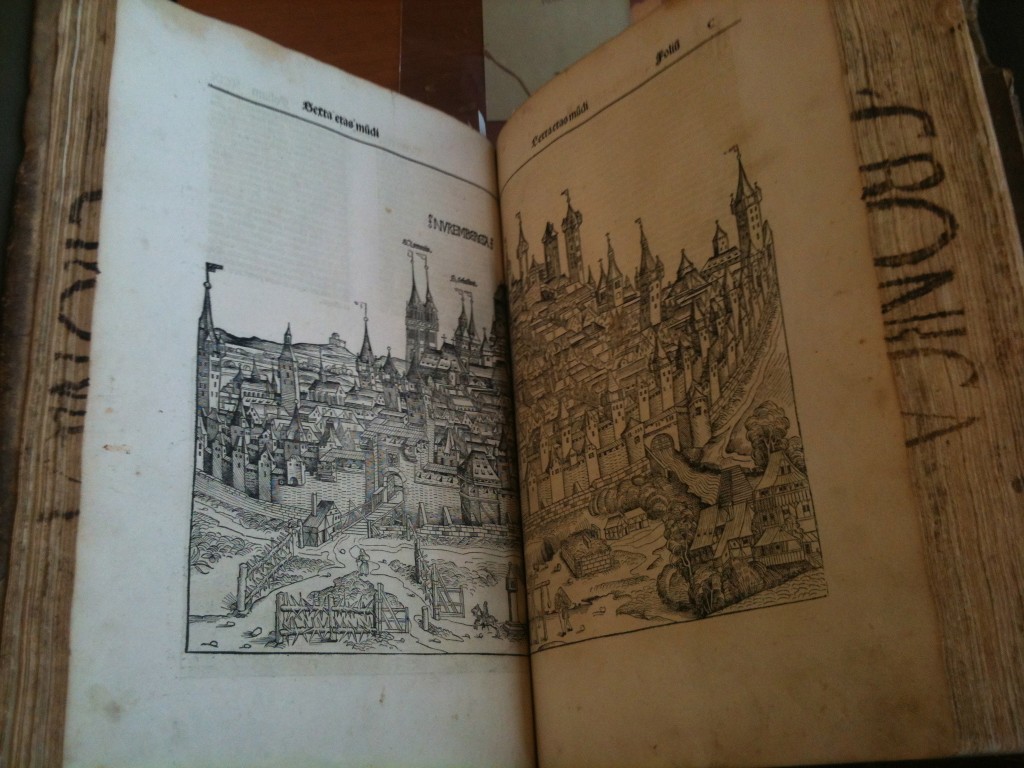

NUREMBERG CHRONICLE, or Hartmann Schedel’s Registrum hujus operis libri cronicarum (Nuremberg, 1493) D17.S315 1493

The Nuremberg Chronicle was an early printed book (or incunabulum) that served as a kind of illustrated world history. For efficiency, images often were repeated, which meant that the same-looking person might reappear labeled with a different name. The title exists on the fore-edge, rather than the spine. To see more images from inside the book (cities, people, and even a few more monsters) in a colored edition, click here.

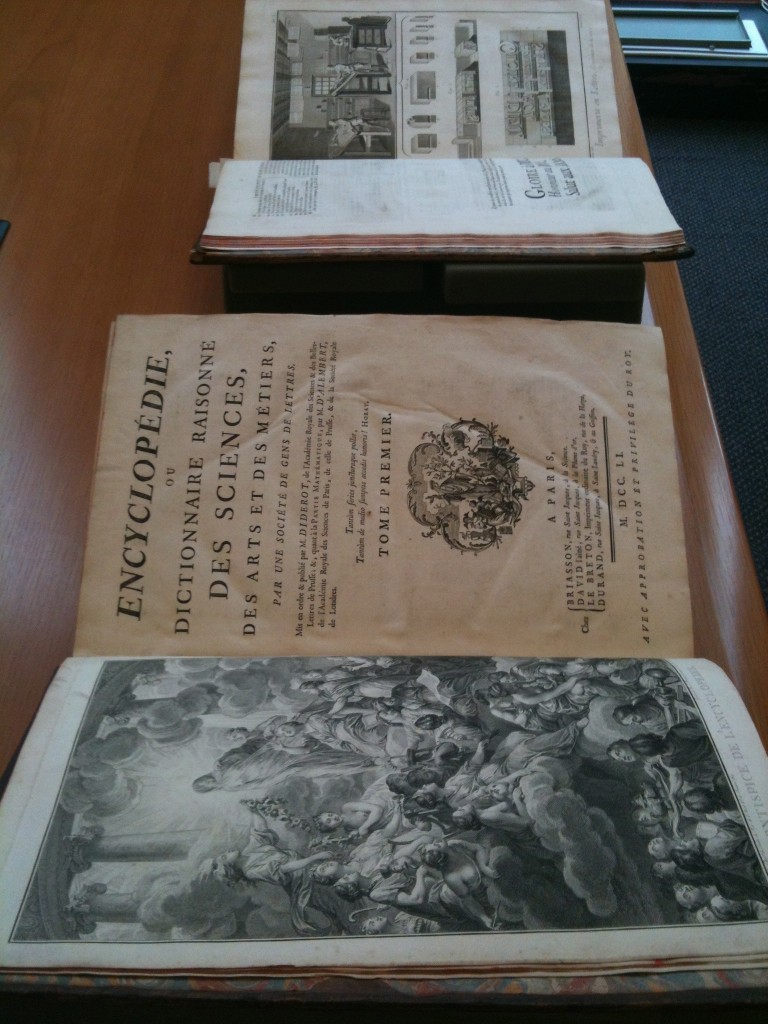

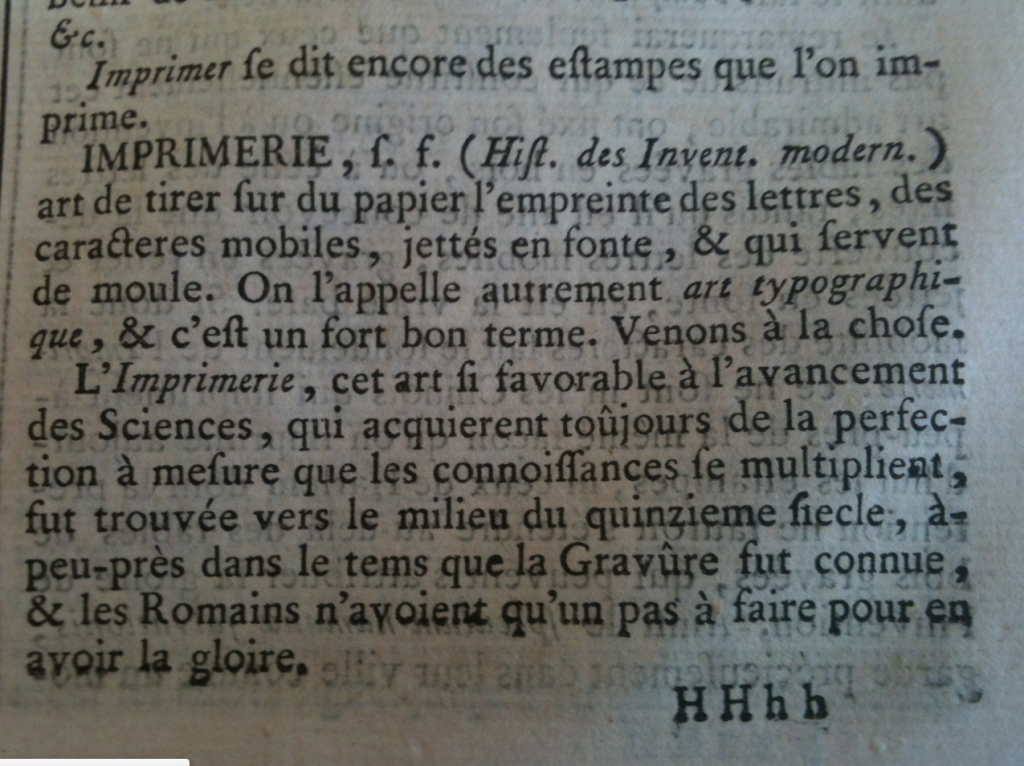

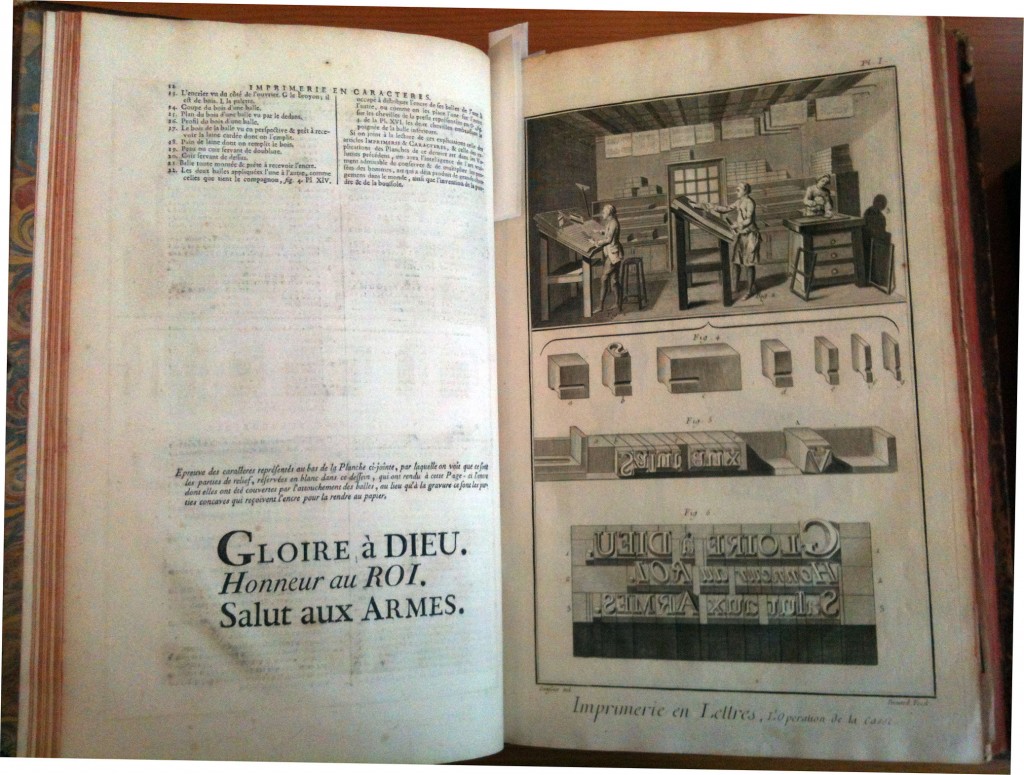

DIDEROT’S ENCYCLOPÉDIE, ou, Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Paris, 1751-1765) AE25.D555 1751

These volumes from Diderot’s Encyclopédie relate to the history of printing, including that entry: “Imprimerie.” (A translation of this entry can be found here.) The volume of plates includes an illustration of a print shop. Beneath it is a composing stick of type (set in reverse) facing the opposite page that illustrates how that type would appear once printed.

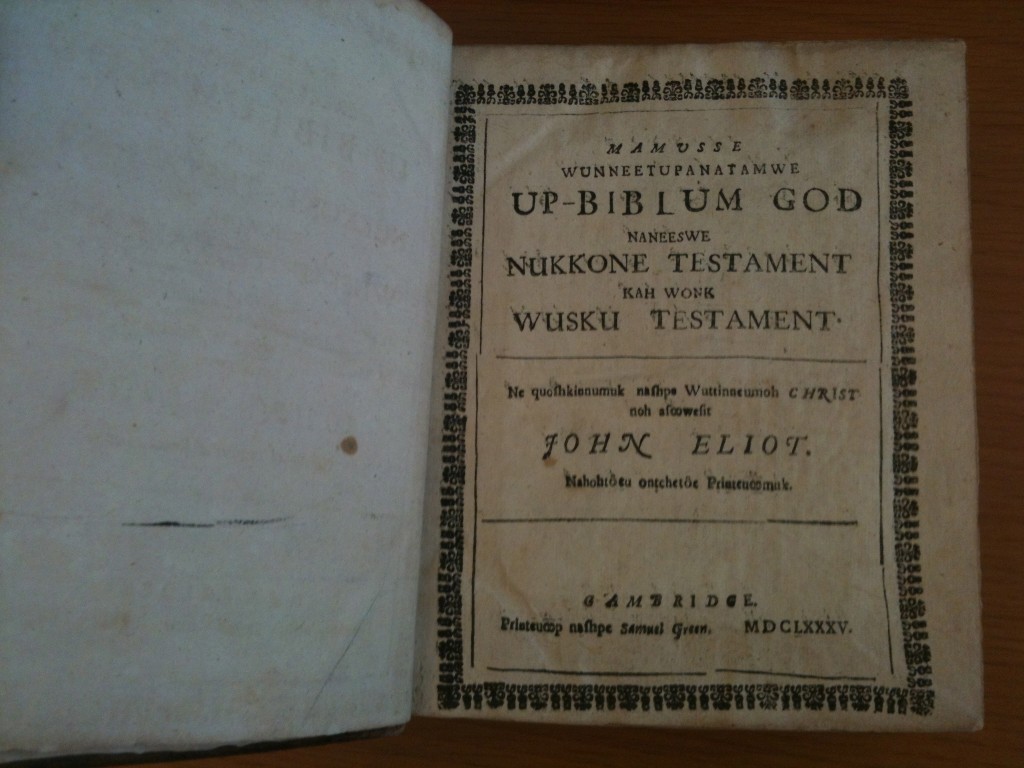

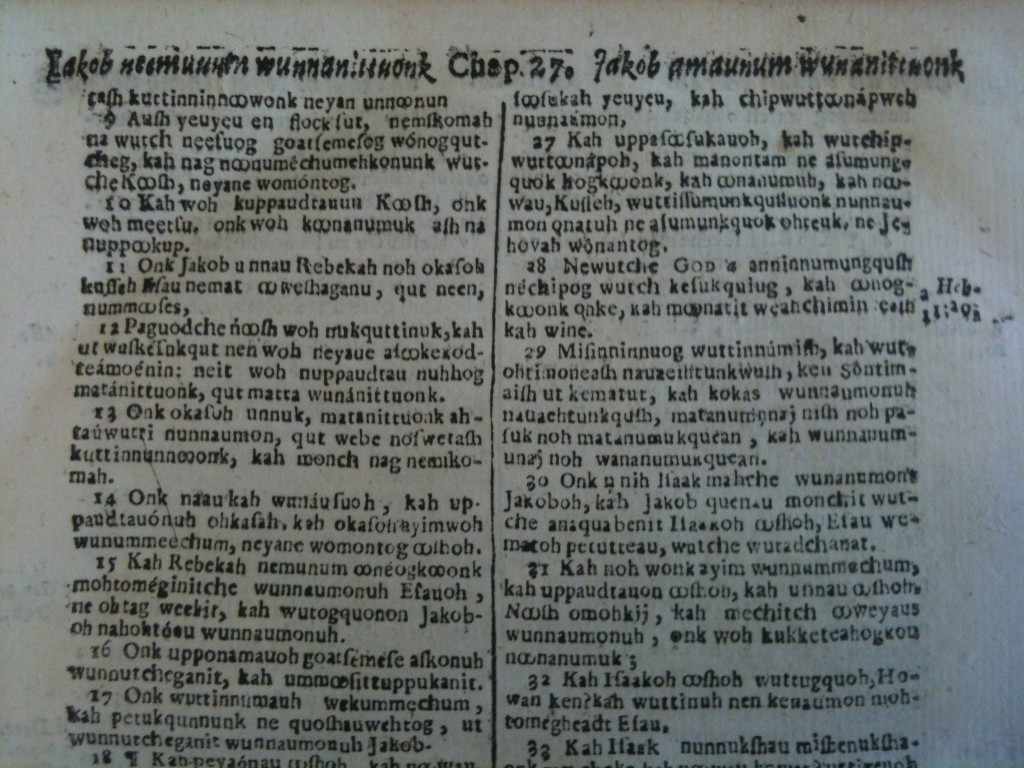

ELIOT INDIAN BIBLE Mamvsse wunneetupanatamwe up-biblum God naneeswe nukkone testament (Cambridge, Mass., 1685) BS345.A2 E42 1685

This bilingual English and Wampanoag Bible was used by MIT student, Jessie Little Doe Baird, SM ’00 to help revive the Wôpanâak language.

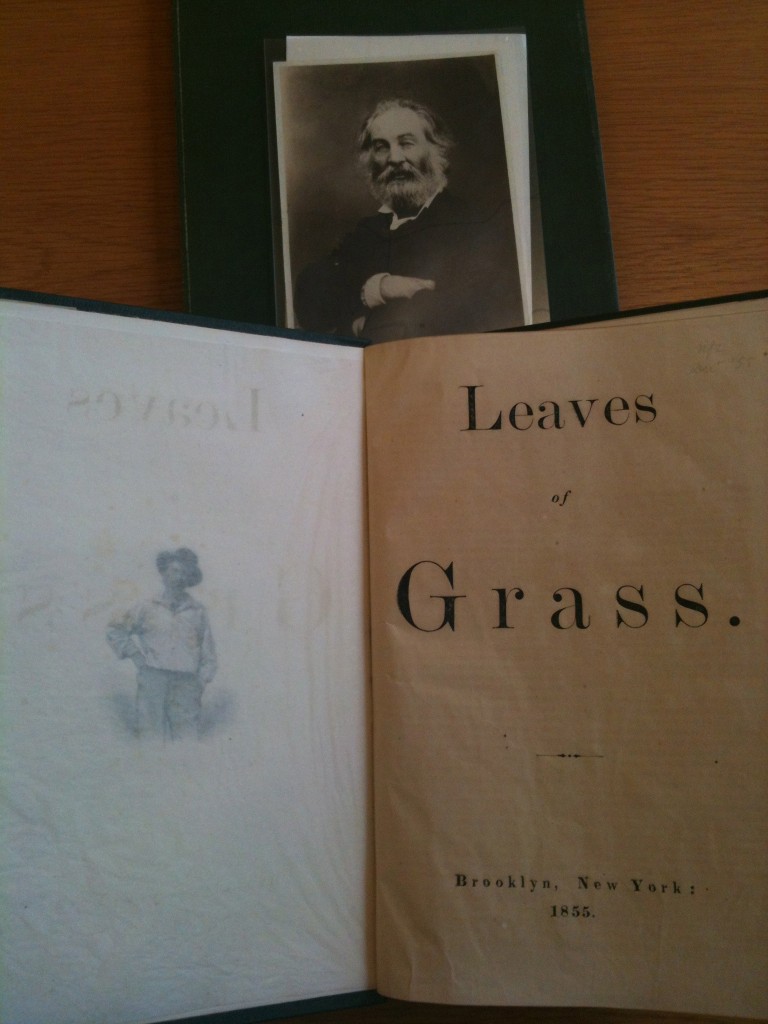

WALT WHITMAN, LEAVES OF GRASS (Brooklyn, 1855) PS3201 1855

This is a first edition of Whitman’s famed collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass. A number of editions appeared during his lifetime ~ and since!

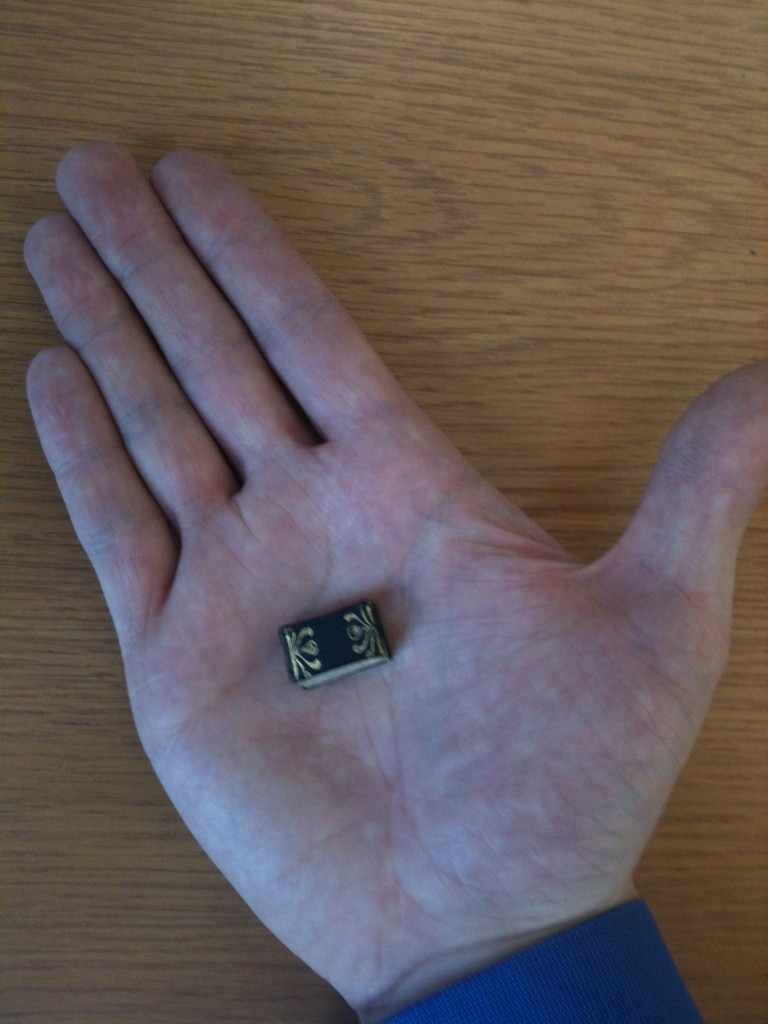

MINIATURE BOOKS Galileo Galilei’s Galileo a Madama Cristina di Lorena (Padua, 1897) BS480.G28 1897

Other examples of miniature books in MIT’s collection include the collected speeches of Abraham Lincoln. A wonderful repository of miniature books can be found here.

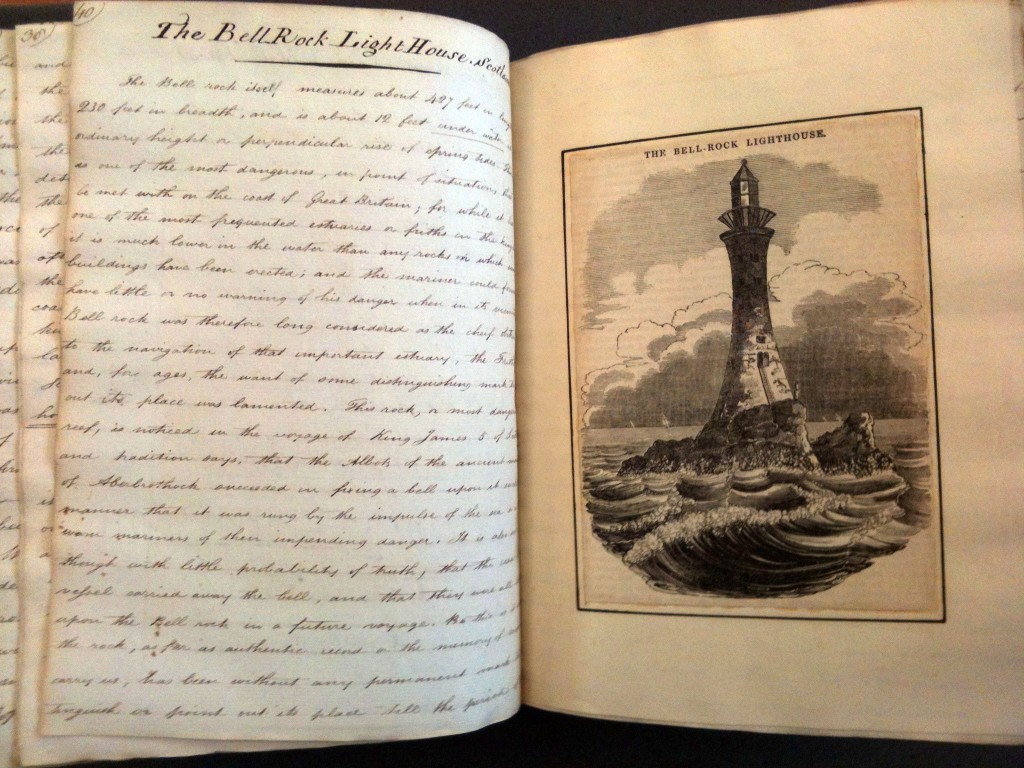

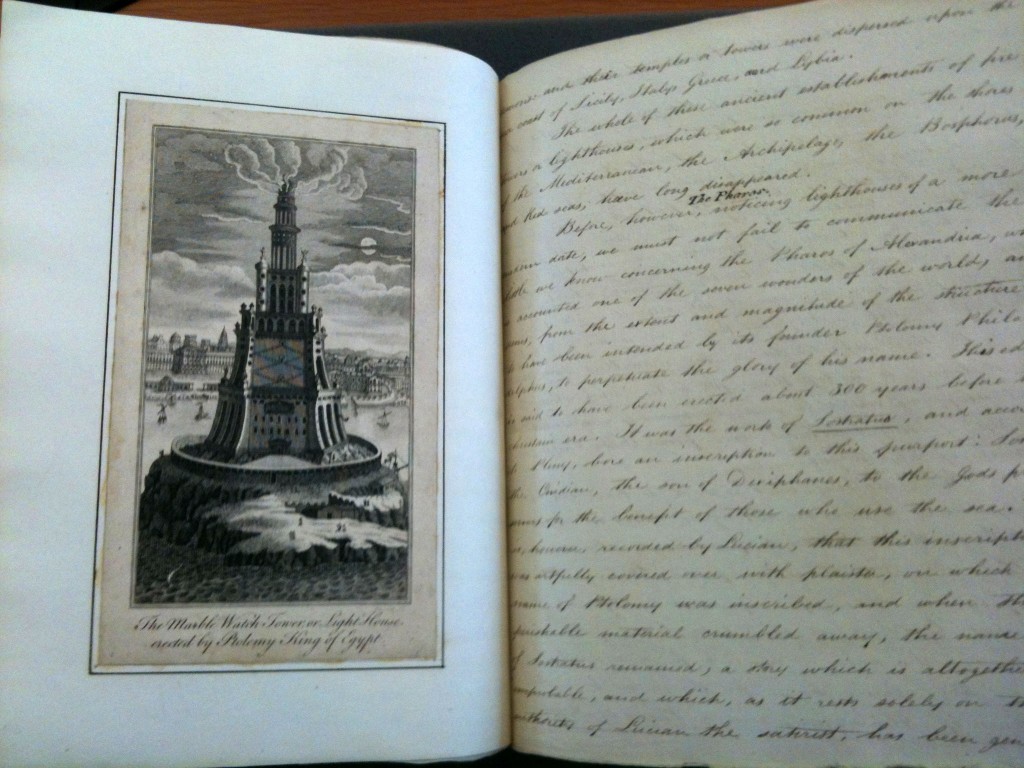

SCRAPBOOKS Remarkable light-houses, and beacons, in various parts of the world (ca. 1832-1844) Uncataloged

For practices like scrapbooking, see also commonplace books and extra-illustration.

AUTHORS MEET READERS

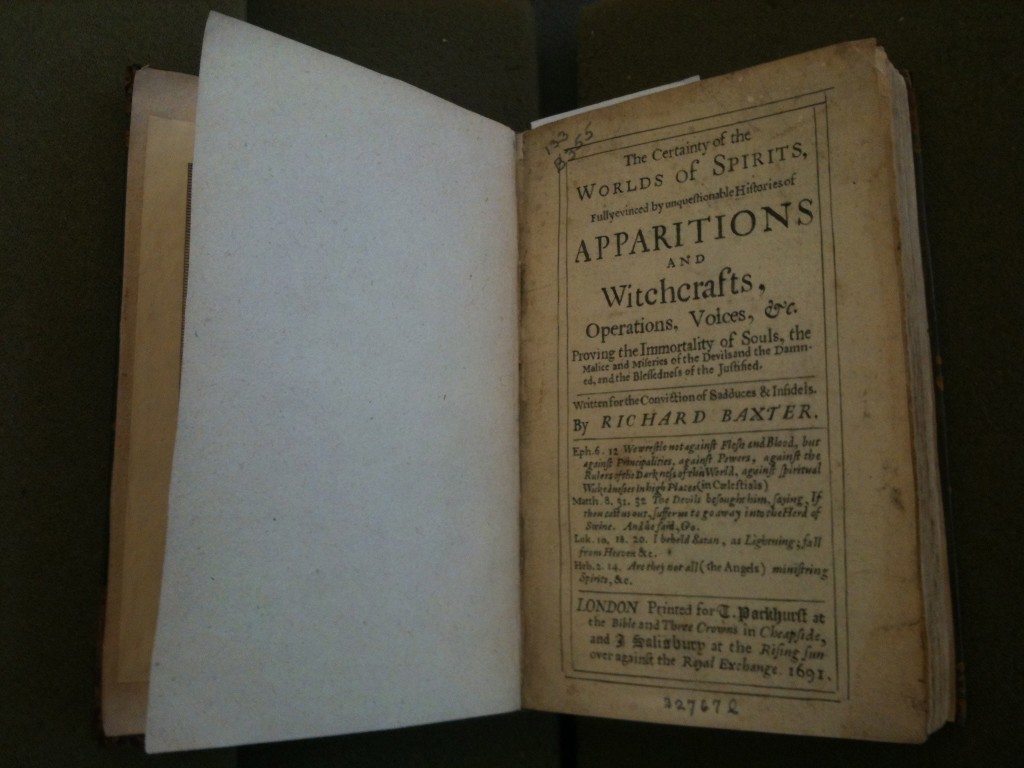

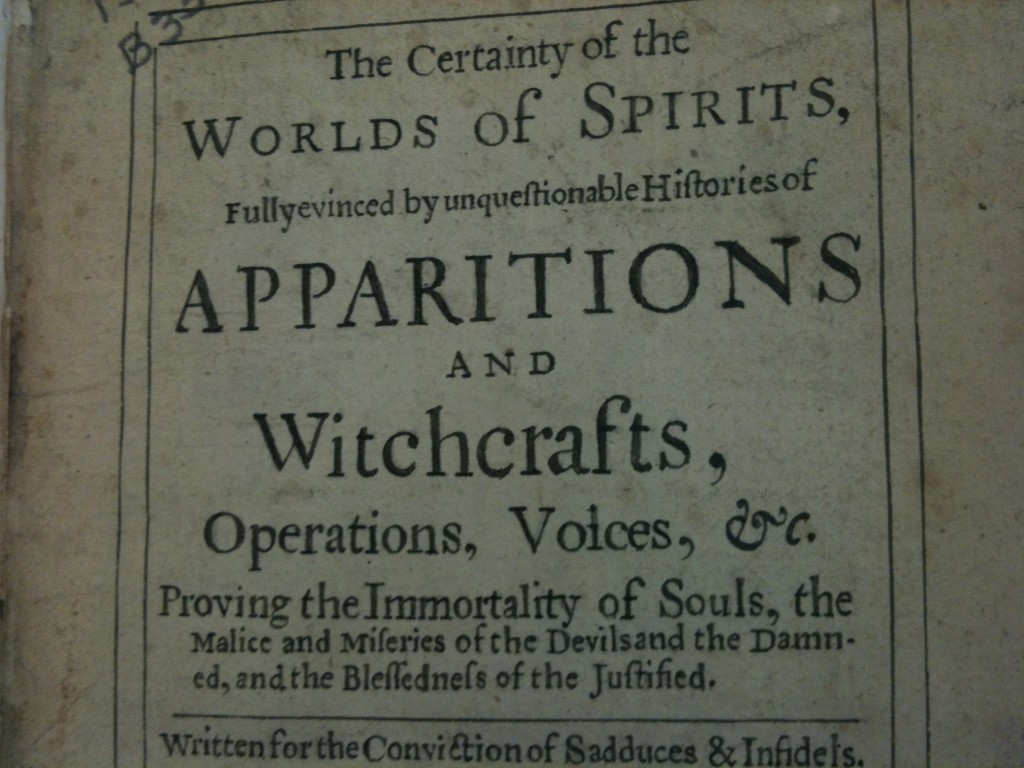

There are many interesting ways that readers interface with texts. Here is one case where the title page was reproduced by hand in ink, hard to notice unless looked at closely. (This particular text was used not far from here in its day in Salem, MA.) Richard Baxter’s The Certainty of the Worlds of Spirits (London, 1691) BF1445.B39 1691

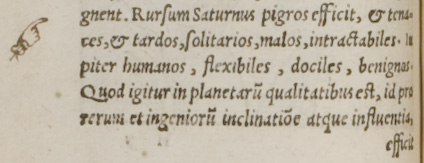

Manicules Johannes Indagine’s Introductiones apotelesmaticae elegantes” by Johannes Indagine (Frankfurt, 1551) BF910.I53 1551

An early means of highlighting, using your own personalized pointing hand (manicule) to draw attention to interesting parts of the text.

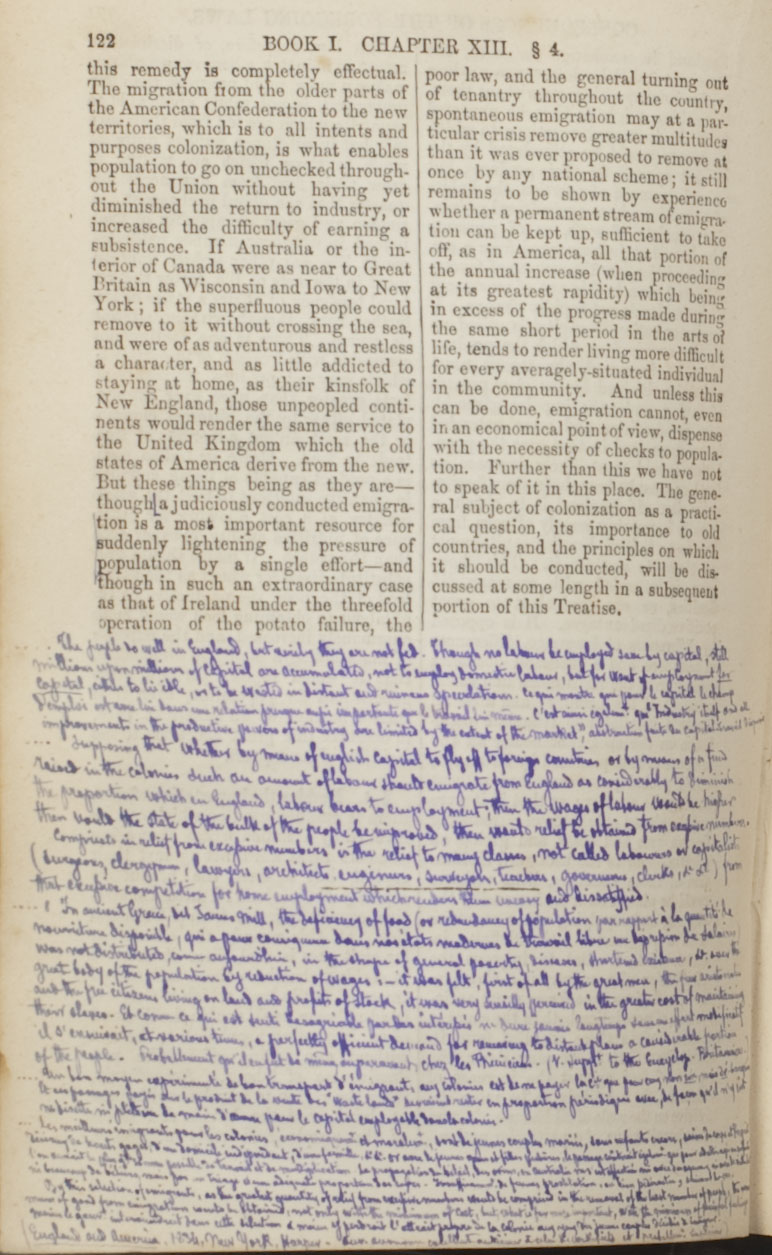

Marginalia John Stuart Mill’s Principles of political economy (London, 1880) HB161.M645 1880

Marginalia in this particular text (small as microscript) is in both English and French.

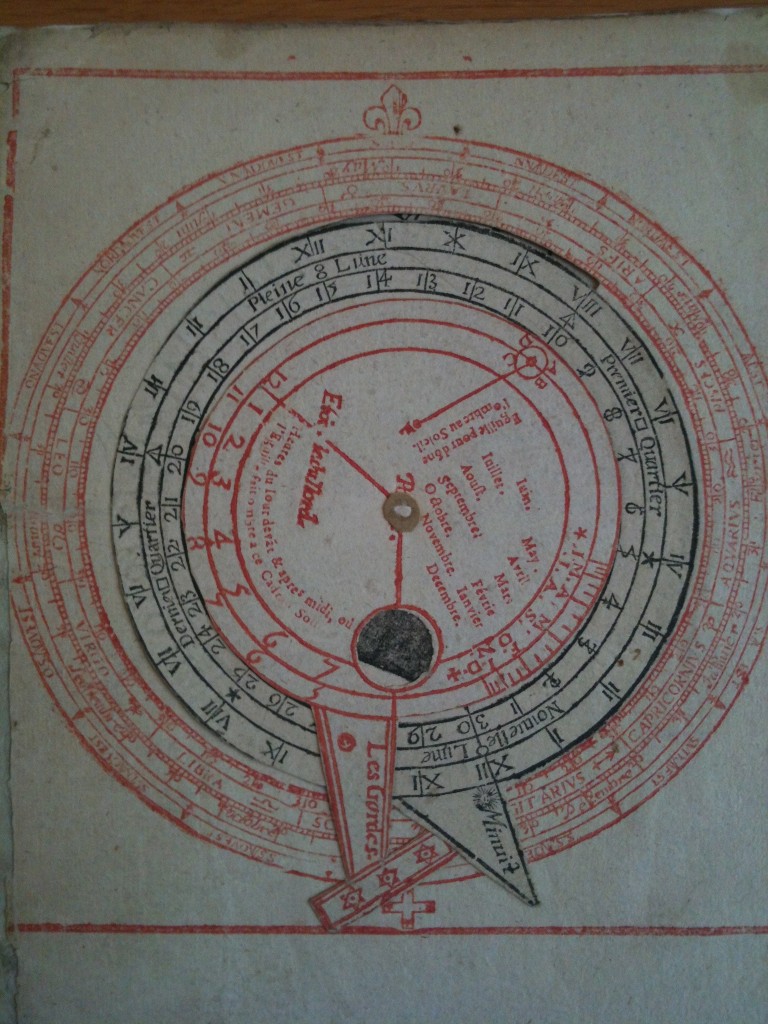

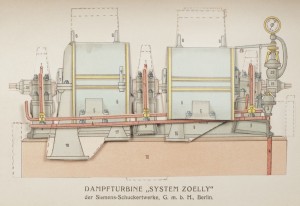

VOLVELLES & MOVEABLE PARTS Jean Oursel’s Le grand guidon et tresor journalier des astres (Rouen, 1680?) CE91.O978 1680 and W. Häntzschel-Clairmont’s Die elektrotechnische Praxis (Berlin, 1907) TK145.H36 1907

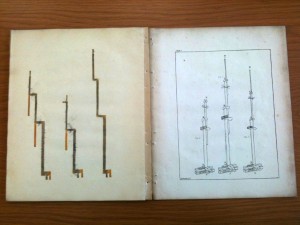

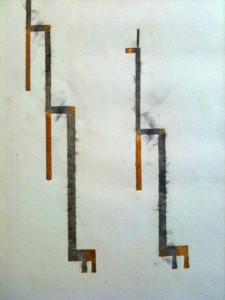

To learn more about volvelles, see here and here. Given its technological bent, might these somehow anticipate future directions of the book? What about this next book that seems to conduct electricity? W. Snow Harris’s Observations on the effects of lightning on floating bodies (London, 1823) OVRSIZE TH9061.H37 1823

All these and more will be on display at the Open House on Friday, May 4, from 10:00-11:30 a.m. Come and see these items in person, talk with librarians, and discover more about how to access these treasures on your own after the Symposium. In addition to the Reading Room display, visitors will be welcome to visit the Conservation Lab and talk to conservators about preservation practices and techniques.

Special thanks to Stephen Skuce, Patrick Olson, and their colleagues for helping to plan the Open House. Photos in this post by Gretchen Henderson and Patrick Olson, with permission by the Archives.

In this particular text (small as microscript) amazing!

One of the most interesting aspects of the old books shown here is their legibility. Compared to the collections of modern printed books which most of us personally maintain — yellow(ed) & brittle & crumbling Penguins from the 1960s & 70s, ditto Pelicans from the 70s & 80s — even Everyman and the rest from the Edwardian and Victorian eras — those much older works even today are crystal-clear models of mise-en-page, graphic design, good organization, user-friendliness. While by contrast everything produced since Victoria ascended and they started using acidic paper is disappearing, fast…

So I hope you will give some thought, here and in your conference, to preservation — of both the print and the digital — the print because so much of it so rapidly is disappearing, we’ve got a big lacuna / hole opening up now where the historical record of our 1830-1960 era ought to be… due as much to misguided “copyright” notions, perhaps, as to the depredations of acidic paper… — and as to the digital, “deleting” all that does not take a pulsar bomb merely the push of a button now will do it… although a similar but better-guided push of another button can duplicate & preserve that archive, now, for generations… Our choice.

Marginalia is another aspect of the old books which may be of great interest here to fans of the new — as illustrated by the scribbling in the Mill’s Principles of Political Economy (1880) edition offered above…

Most of us have been trained since childhood _never_ to “write in a book”. It’s part of a panoply of social practices — like the infamous librarian’s “Shhh!” which prevents us from discussing what we read — or the wonderful BIbliothèque Nationale sign, laughed-at by Umberto Eco (“De bibliotheca”, 1986), which sternly warned, “No Reading Room books in the Reference Room / No Reference Books in the Reading Room!” — which forever have inhibited our reading.

Or at least _my_ reading… One of my student life’s favorite guilty-pleasures was scribbling notes in the margins of my books: it was the only way I could “become involved” with the texts they contained, after long nights of studying them — I read sociology, and political theory — Kelsen was OK because he was so clear, but just _try_ reading Talcott Parsons, or Weber, or Hegel(!), without doing a little marginalia at least to stay awake. Never in library books… but the used Penguins I’d buy for a quarter apiece at the Co-op or The Strand got filled… I still have some of them.

That personal involvement with their texts is the key to book-learning, tho, I am convinced. And now digital technique truly “unbinds” a text — in one of the senses intended by this “Unbound” conference-title — by enabling highlighting and the writing of notes.

Also the serendipitous parallel research of simultaneous linkages and Web-searching — reference librarians’ dreams & nightmares, both — but that’s another topic…

An old — in several senses too — friend donated his wonderful & well-known collection of ancient marginalia to a library, several years ago. Marginalia is an ancient practice, one very useful always to its many practitioners. One problem with “bound” books always has been that you can’t just “read” them — to truly understand what they say you have to “get into” the texts they contain, sometimes following frowned-upon practices — now that digital has “unbound” texts, that process of understanding has become much easier and far more productive.

the lightning rod/ship’s mast diagram/picture in W. Snow Harris his Observations on the effects of lightning on floating bodies (London, 1823) —

an early — and even a first — “printed” circuit?