(A guest post by Alana Kumbier, Library & Technology Services, Wellesley College)

(A guest post by Alana Kumbier, Library & Technology Services, Wellesley College)

I spent last Sunday afternoon at the Washington Street Art Center in Somerville, celebrating the arrival of spring with a roomful of artists and zine-makers. I had my doubts about whether this small, local event — the Spring Zine Thing — could compete with the lure of the outdoors on one of the season’s first hot, sunny days. When I walked up to the Center and saw folks waiting around for the doors to open, I realized I’d underestimated the appeal of zines, and of zine-fair camaraderie. I spent the afternoon chatting with other zine- and comics-makers, watching readers connect with zines, meeting people from neighborhood organizations and businesses, trading design and binding tips, and, best of all, making zines. The event’s organizers, Megan Mary Creamer and Marissa Falco had stocked a corner table with supplies — paper, scissors, letraset transfers, pens, crayons, glue sticks, a long-arm stapler, and a typewriter — for on-the-fly zine-making. In another corner, a group of participants worked on zines they’d started at Ladyfest Boston. At other tables, artists sketched the scene and worked on collages. When we packed up our zines and headed out the door at closing time, the room was still full, and there were several clusters of friends hanging out, relaxing and chatting in the Art Center parking lot. The Spring Zine Thing made local interest in zines visible, and emphasized the vibrant nature of the community supporting them.

Observing what happened at the Spring Zine Thing, noting the influx of new volunteer librarians at the Papercut Zine Library in Cambridge, and looking forward to the Somerville Arts Council’s zine-themed Salon, I want to say that zines are making a comeback (at least in Boston & its suburbs). But they never really went away.

Because I live in a bigger city, have internet access, and a wider social network than I did in the mid-late 1990s, I know more zinesters now than I did during my initial foray into zine culture. Some of these folks have been making zines for decades. Others, like me, made them in high school, college, or early adulthood, took a break, and and are returning to zines in their mid-thirties. Others are just starting out, eager to connect with radical histories and communities. More than a few of us are professional educators, graphic designers, and librarians, with access to institutional resources, faculty collaborators, and pedagogical spaces for teaching and learning about zines. Because zines don’t require much in terms of supplies, instructional time, or classroom (or other) space, it’s relatively easy to make them at home, on campus, or in the community. Zine libraries and archives require much more of an investment, but they, too, can be scaled to meet the needs of a particular community — and can operate in and outside of conventional institutions (i.e., academic or public libraries).

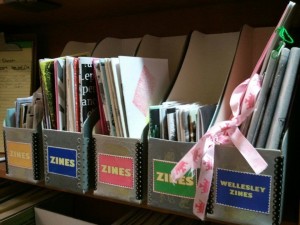

In the past year, I’ve collaborated with faculty, students, and staff at my institution, Wellesley College, on a variety of zine-based projects and events. We’ve incorporated zine projects in introductory and upper-level women’s and gender studies courses, offered zine workshops to students in the library’s Book Arts Lab, and this spring, student organizations collaborated on hosting a feminist zine fair. As a research and instruction librarian, I spend a good deal of my day in the realm of the digital: helping students and faculty use online tools and resources; developing strategies for teaching and learning in hybrid material-digital environments; creating online research guides; and troubleshooting problems with e-books, or our learning management system, or citation tools like Zotero and EndNote. Zine projects, organized around self-published, material texts, disrupt this digital-immersion in some delightful ways.

When I teach a women’s and gender studies class about zines, I’m able to engage students in conversations that rarely fit into a conventional research instruction session. Though most of the students are unfamiliar with zines, they immediately understand the potential of the medium: how it authorizes its creators to pursue questions they’re passionate about, to offer analyses based on research and critique, to write for a community of other zine makers, and to create something tangible to share with their peers. We talk about feminist knowledge production practices, the benefits and drawbacks of self-publishing, intellectual property concerns, and the political, cultural, documentary, and educational work that zines do in the world. We get into debates about zines vs. blogs as feminist activist tools — and challenge the assumption that a person might make or read in one medium but not the other. We talk about the Queer Zine Archive Project and the People of Color Zine Project, and consider how online archives extend the life of these ephemeral objects, making old zines accessible to readers (like my students) who weren’t around to read them, and offering spaces for archiving and sharing new zines.

When students come to the library to make zines in the Book Arts Lab, they discover one of our campus treasures: a workshop full of printing presses, wood and metal type, bookbinding tools and many other (less-spectacular) supplies for zine-making. And they meet our book arts director, Katherine McCanless Ruffin, who can serve as a teacher and guide for future adventures in self-publishing. Most importantly, when students make zines with us, they claim the library as a space for making and creating knowledge, texts, and community.

As they produce their zines at the end of the semester, I’m proud that our students join a constellation of zine-makers, radical librarians, teachers and archivists, feminist scholars, and community arts organizers dedicated to this form of knowledge articulation, material-cultural production, creative work, and political action. And that they get their hands on some scrap paper, markers, glitter and glue in the process.