It seems to me that the future of the book is here already — what remains is for us to figure out what to do with it.

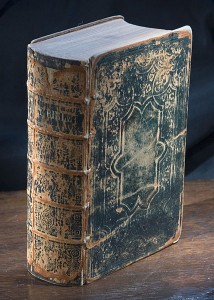

The codex, a collection of pages presented in such a way that they can be accessed independently, is a mature technology, and an efficient way of encoding and storing information for a variety of uses. Even in the age of the ebook, the codex seems likely to have a long future ahead of it. Ebooks will replace codices in the contexts in which they are more efficient — supplanting cheap disposable paperbacks and magazines, taking over the self-publishing industry, capturing a large segment of the popular fiction market. Codices will continue to be used in the contexts in which their virtues are more important — low-power, long-term storage, easy sharing, easy random access, collectability, and display. Technical and legal advances will continue to increase the scope of ebooks, but they’re never going to supplant the codex entirely.

The codex, a collection of pages presented in such a way that they can be accessed independently, is a mature technology, and an efficient way of encoding and storing information for a variety of uses. Even in the age of the ebook, the codex seems likely to have a long future ahead of it. Ebooks will replace codices in the contexts in which they are more efficient — supplanting cheap disposable paperbacks and magazines, taking over the self-publishing industry, capturing a large segment of the popular fiction market. Codices will continue to be used in the contexts in which their virtues are more important — low-power, long-term storage, easy sharing, easy random access, collectability, and display. Technical and legal advances will continue to increase the scope of ebooks, but they’re never going to supplant the codex entirely.

If you don’t believe me, consider the observed fact that vinyl records are back in the music industry in a major way. Although the economics and culture of music-publishing are not the economics and culture of book-publishing, the changes wrought in one are nevertheless likely to have parallels in the other. In a world where the ease of digital distribution allows content creators to self-fund the production of their work by selling limited-edition collectibles to their most dedicated fans, that very ease of distribution is a liability if digital media forms are to be the sole means by which creative works are distributed. The codex’s scarcity and irreproducability become key features of its utility.

I find it increasingly difficult to talk or think about “ebooks” as distinct from “books”, rather than as a subset. We have had words distinguishing different book forms for a while — audiobooks and comic books and picture books. A “book” is a Platonic object, words and pictures arranged in some particular order; a paper book is no longer the unmarked medium. I have read a book, whether I read it on a paper “screen” or a laptop screen or a phone screen or an ereader screen.

What interests me is when it ceases to be the case that a book reproduced on paper contains the same information as a book reproduced on a computer screen. As we increasingly read books through devices capable of reproducing not just words and pictures but music and video, we will begin to see these forms of media incorporated into our books, and into our concept of what a book is. Imagine a film textbook containing relevant clips of the films discussed, or a novel where each chapter also embeds the original song from whose lyrics its epigraph is taken. These are books just as surely as anything to which we might today give that name. As we increasingly read books through devices capable of more complex interactions than those admitted by the codex form, our books are going to come to integrate these interactions.

One of my favorite recent examples of this confusion is “don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story,” by Christine Love. In presentation, it is a visual novel, a form originally popular in Japan — a video game with a focus on text and mostly-static pictures where the player is periodically presented with choices of action or dialogue which affect the outcome of the story. “Don’t take it personally” is a relatively short story with a small number of branch points; much of what it does at the level of its framing narrative could be done in a straightforward, if expensive, fashion in the codex form. (Even the interactivity: remember the Choose Your Own Adventure books popular a decade or two ago?)

One of my favorite recent examples of this confusion is “don’t take it personally, babe, it just ain’t your story,” by Christine Love. In presentation, it is a visual novel, a form originally popular in Japan — a video game with a focus on text and mostly-static pictures where the player is periodically presented with choices of action or dialogue which affect the outcome of the story. “Don’t take it personally” is a relatively short story with a small number of branch points; much of what it does at the level of its framing narrative could be done in a straightforward, if expensive, fashion in the codex form. (Even the interactivity: remember the Choose Your Own Adventure books popular a decade or two ago?)

What couldn’t be reproduced without ruinous expense and effort is the game’s internal Facebook-like social network. Throughout the story, the characters are sending public and private messages to each other, both commenting on the framing narrative and providing their own narratives. The player character (and thus the player) is encouraged to switch context out of the framing narrative to keep abreast of these parallel narratives. The parallel narratives provide critical information which isn’t available in the framing narrative, and the framing narrative relies on and calls attention to this fact. (Multiple reviews have complained about being distracted by the constantly blinking notification icon for the in-game social network, which seems to me to be one of its goals.)

One of the game’s primary themes is the societal and cultural changes brought about by social media, and the ethics of using the information it provides. Given that we do not yet experience social media through paper books, presenting this story in that fashion would have lost the immersion provided by presenting it in the fashion that the characters experience it. The richness of the choices presented to the player could also not be easily represented in paper — each decision to read messages is a distinct choice, with implications for the player’s experience of the framing narrative. (One moment late in the game where choosing to read messages is a minor plot point drives home just how much the fact of that choice matters.) The ability to backtrack and follow other story branches, or replay the game making entirely different choices, enables the player to understand the effect their choices had (or failed to have). Even the incidental elements add to the story — the music in particular is well used to enhance the emotional impact of key moments.

I think that, if we are willing to accept a novel with embedded music or a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book as a “book”, then “don’t take it personally” is just as much a book. At the same time, “don’t take it personally” is a book embodying a story which could never have been presented with the same impact in the codex form. What interests me more than anything about the future of the book is what other stories exist like that. What stories can we now tell now in our new book forms which we couldn’t have told before? What stories can we tell now which we couldn’t even have imagined before? What stories will we choose to tell?

It’s going to be a very interesting future.

Kellan Sparver blogs about science fiction, writing, video games, and whatever else he finds interesting at KellanSparver.com.

[…] post is cross-posted from the blog of Unbound: Speculations on the Future of the Book, a symposium at MIT running […]