A guest post by Mara Mills, Assistant Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication, NYU. Mills is currently researching the history of talking books and reading machines.

The demand for “print access” by blind people has transformed the inkprint book. Some scholars today distinguish between e-books and p-books, with the “p” standing for print, yet already by the early twentieth century blind people and blindness researchers had partitioned “the book” and “reading” into an assortment of formats and practices, including inkprint, raised print, braille, musical print, and talking books. In turn, electrical reading machines—which converted text into tones, speech, or vibrations—helped bring about the e-book through their techniques for scanning, document digitization, and optical character recognition (OCR).

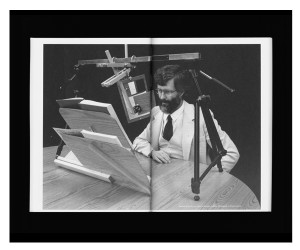

The first such reading machine, the Optophone, was designed in London by Edmund Fournier d’Albe in 1913. A “direct translator,” it scanned print and generated a corresponding pattern of tones. Vladimir Zworykin (now known for his work on television) visited Fournier d’Albe in London in the 19-teens and saw a demonstration of the Optophone. At RCA in the 1940s, he built a reading machine that operated on the same principles, followed by an early OCR device that spelled out words letter by letter using a pre-recorded voice on magnetic tape. John Linvill began working on an optical-to-tactile converter—the Optacon—in 1963, partly as an aid for his blind daughter. Linvill soon became chair of the electrical engineering department at Stanford, and the Optacon project became central to early microelectronics research at the university. Linvill and his collaborator, Jim Bliss, believed that a tactile code was easier to learn than an audible one, because the analogy between visible and vibratory print was more direct (both formats being two-dimensional). Extending the technique of character recognition (rather than direct translation), in 1973 Raymond Kurzweil launched the Kurzweil Reading Machine for the Blind, a text-to-speech device with multi-font OCR. As he recalls in The Age of Spiritual Machines, “We subsequently applied the scanning and omni-font OCR to commercial uses such as entering data into data bases and into the emerging word processing computers. New information services, such as Lexis (an on-line legal research service) and Nexis (a news service) were built using the Kurzweil Data Entry Machine to scan and recognize written documents.”

Harvey Lauer, one of the foremost experts on twentieth-century reading machines, was the blind rehabilitation and technology transfer specialist at the Hines VA Hospital for over thirty years. Colleagues Robert Gockman and Stephen Miyagawa have called him “the ‘father’ of modified electronic devices for the blind and the ‘Bionic Man’ of the Central Blind Rehabilitation Center.” Lauer attended the Janesville State School for the Blind, where he studied music and tinkered with electronics and audio components. He earned his B.A. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 1956 and his M.S. in Vocational Counseling from Hunter College the following year. Shortly before his retirement from the VA in 1997, Lauer wrote a speculative paper on the “Reading Machine of the Future.” By that time, personal computers were common and flatbed scanners were becoming affordable for home use. Text-to-speech software was beginning to replace the standalone reading machine. Yet the increasing complexity of graphical user interfaces inhibited blind computer users, and a conservative approach to reading (i.e. tying print to speech) was embedded in commercial OCR software. Lauer advocated a “multi-modal reading aid” with braille, tonal, vibratory, and speech outputs for translating text and graphics. With Lauer’s permission, I’ve excerpted the following selection from his unpublished article.

READING MACHINE OF THE FUTURE

BUT THE FUTURE WON’T JUST HAPPEN

Harvey Lauer

September 12, 1994

From 1964 to the present, I have used, tested and taught fourteen reading machines and many more devices for accessing computers. Working for the Department of Veterans Affairs, formerly the Veterans Administration, I saw much progress and several lessons forgotten.

The system I feel we really need will have a choice of modalities—speech, Braille, large print and dynamic graphic displays. It will be configurable according to the user’s needs and abilities. It will scan pages into its memory, process them as best it can, and then allow us to read them in our choice of medium. Automatic sequencing would be our first choice for easily-scanned letters, articles and books. But it will also let us examine them with a keyboard, a tablet, a mouse or perhaps tools from Virtual Reality. It will offer us any combination of speech, refreshable braille or large print as well as a verbal description of the format or layout. Because we will be able to use that description to locate what we want to read, it will be easier to use than current OCR machines, but not larger. When we also need to examine shapes, we will switch on tonal and/or vibratory (graphical) outputs. As I have noted, examining the shape of a character or icon is far easier than reading with such an output.

In short, the system will offer a three-level approach to reading. The first choice is to have a page or screenful of text recognized and presented either as a stream of data or as data formatted by the machine. We can now do that with OCR machines. At the second level, we can choose to have the machine describe items found on pages or screen displays and their locations. We can have either brief descriptions or descriptions in “excruciating detail.” We can then choose items by name or characteristics. That won’t always be sufficient, so we will have a third choice. We can choose to examine portions of the page or individual items found by the machine, using speech, braille characters, a display of tones, an array of vibrators, a graphic braille-dot display or magnified and enhanced images. Once the basic system is developed, it will constitute a “platform” for people like us to test its practical values and for researchers to test new ideas for presenting information to humans.

It’s 1997. You place a page on your scanner. It could be a recipe, a page from a textbook or part of a manual. You direct the machine to scan it into memory. You suspect that it isn’t straight text, so you don’t first direct the machine to present it in speech or braille. You request a description of the format and learn that the machine found two columns of text at the top, a table, and a picture with a caption. It also noted there were some tiny unidentified shapes, possibly fractions.

You then turn to your mouse (or other tracking device) which you move on an X/Y tablet. (This concept of a tablet was best articulated by Noel Runyan of Personal Data Systems in Sunnyvale, California.) You switch to freehand tracking and examine the rest of the page for gross features, without zooming. You find the table, plus what appears to be a diagram and some more text. With the mouse at the top of that text, you switch to assisted tracking. Now the system either corrects for mistracking or the mouse offers resistance in one or the other direction, depending upon your choices. As you scan manually, the text is spoken to you. After reading the block of text, you read the caption and examine the table. You find that some of the information needs to be read across columns, and some makes sense only when read as columns. You are thankful that you don’t have an old-fashioned OCR, screen reader and Optacon to tackle this job.

Then you find a longer piece of data you want to copy, so you “block and copy” it to a file. In examining the diagram, you find tiny print you want to read, but the OCR can’t recognize it, so you zoom in (magnify) and switch to the mode in which shapes can be examined. Depending on your equipment and your abilities, you can have them presented as vibrating patterns on an Optacon array, as tone patterns, as a graphic, dot image on a rapidly-refreshing array of braille dots, or as a combination of those modalities. You may or may not have the skill to read in this way; few people make the effort to develop it nowadays. What you do is examine the characters slowly and trace the lines of drawings in which you are interested.

With the new instrument, we won’t have to give up nearly as often and seek sighted assistance. Optacon users will no longer have to remove the page and search about with camera in hand as if reading a map through a straw. Computer users will still have our screen access software. OCR users will still have their convenient, automatic features. However, when you use a current OCR machine to scan a page with a complex format, the data is frequently rearranged to the point where it’s unusable. Such items as titles, captions and dollar amounts are frequently scrambled together. It makes me feel as if I am eating food that someone else has first chewed. With the proposed system, when its automatic features scramble or mangle our data, we can examine it as I have described.

The exciting point is this: The proposed integrated system with several optional modules would harness available technology to allow us to apply the wide gamut of human abilities among us to a wide gamut of reading tasks. In 1980, I presented this idea in a paltry one-page document added to an article about reading machines. I then called it the Multi-dimensional Page Memory System. I’ve given it a new name—the Multi-modal Reading Aid.