1. I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us. We need the books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished to forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.

2. And yet the first obstacle is certainly the book itself—clunky and musty and shouting nonsense all the time. Thus the first solution is to re-make the book into a two-way communication node; cast it as self-aware in some small sense, gesturing toward the contradictions of its authorial positions.

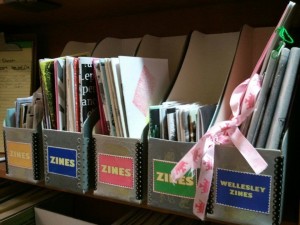

3. A book is a set or collection of written, printed, illustrated, or blank sheets made of ink, paper, parchment, or other materials, usually fastened together to hinge at one side. A single sheet within a book is called a leaf or leaflet, and each side of a leaf is called a page. A book produced in electronic format is known as an electronic book or e-book.

4. A store where books are bought and sold is a bookstore or bookshop. Books can also be borrowed from libraries. In 2010, Google estimated that there were approximately 130 million distinct books in the world.[1]

5. His novel BLANK was published by Jaded Ibis Press in March 2011. The novel consists of 20 chapter titles that Schneiderman has claimed in an HTMLgiant.com interview follows morphological structures in line with the work of Vladimir Propp. The titles, such as “A Character” or “Another Character”, are separated by blank pages that contain 20 randomly spaced pyrographic or burn illustrations by artist Susan White. Additionally, the work has a “soundtrack” of three remixed Bach tracks from DJ Spooky. These tracks are available as part of a $7500 fine-art edition of the novel, which comes encased in a plaster. The plaster must be broken by the reader to access the blank novel. Jaded Ibis does full-spectrum publishing, and Blank will be available in an e-book edition and a color edition to supplement the black-and-white commercial edition.

6. E Ink (electrophoretic ink) is a specific proprietary type of electronic paper manufactured by E Ink Corporation, founded in 1997 based on research started at the MIT Media Lab. It is currently available commercially in grayscale and color[1] and is commonly used in mobile devices such as e-readers and, to a lesser extent, mobile phones and watches.

7. BLANK signals Schneiderman’s move toward conceptual writing, which is also reflected in a number of his recent web publications called the “Un-Death of the Author” series. In these, Schneiderman publishes well-known literary works under his name, as per the prologue to The Canterbury Tales (in Middle English), that appear on a 2010 edition of the website Publishing Genius.

8. The adverb [SIC]—meaning “intentionally so written”—first appeared in English circa 1856.[2] It is derived from the Latin adverb sīc, which contains a long vowel and means “so”, [note 3] “thus”, “as such” or “in such a manner”.[3] In English, [SIC] is a homophone of [SIC]k /ˈsɪk/; its Latin ancestor is pronounced more like the English word seek [ˈsiːk].[4]

9. The Amazon Kindle is an e-book reader developed by Amazon.com subsidiary Lab126 which uses wireless connectivity to enable users to shop for, download, browse, and read e-books, newspapers, magazines, blogs, and other digital media.[1] The Kindle hardware devices use an E Ink electronic paper display that shows up to 16 shades of gray, minimizes power use, and simulates reading on paper.

10. In one early instance, a letter written in July, 1876 by Dr. Enoch Mellor to the editor of the Literary Churchman discussed “the cheap insinuation of ignorance which can lie in a bracketed [SIC].”[5]

11. BLANK is the first term in Schneiderman’s DEAD/BOOKS trilogy. His first sequel to BLANK, titled [SIC], consists of three divisions.

12. The first division includes public domain works Schneiderman published under his name which appear to originate from other writers who are not Schneiderman. For instance, Schneiderman published one of the earliest Old English poems, “Cademon’s Hymn,” the prologue to The Canterbury Tales, and “Tyger, Tyger,” as well as sections of Moby Dick; or, The Whale, Ulysses, and appropriately, “Kubla Khan; or, A Vision in a Dream: A Fragment.”

13. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the verb form of [SIC], meaning “to mark with a [SIC],” emerged in 1889, citing E. Belfort Bax‘s work in The Ethics of Socialism as one of the early examples.[1] That piece by Bax, “On Some Forms of Modern Cant,” had actually appeared even earlier in Commonweal, published in 1887.[6]

14. This 1996 law, also known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, Sonny Bono Act, or the Mickey Mouse Protection Act[2] effectively “froze” the advancement date of the public domain in the United States for works covered by the older fixed term copyright rules. Under this Act, additional works made in 1923 or after that were still protected by copyright in 1998 will not enter the public domain until at least 2019.

15. The third division of [SIC] includes works under in the public domain after 1923, the year frozen by the Mickey Mouse act, and so includes Wikipedia pages (which comprise much of the paper you are now reading), Supreme Court verdicts related to intellectual property, genetic codes, and other untoward appropriations.

16. Usage of [SIC] greatly increased in the mid-twentieth century.[7] For example, in state-court opinions prior to 1944, the Latin loanword appeared a total of 1,239 times in the Westlaw database; in those from 1945 to 1990, it appeared 69,168 times.[8] The “benighted use” (see Form of ridicule) has been cited as a major factor for this increase.[8]

17. “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” (original Spanish title: “Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote”) is a short story by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges.

18. It originally appeared in Spanish in the Argentine journal Sur in May 1939. The Spanish-language original was first published in book form in Borges’s 1941 collection El Jardín de senderos que se bifurcan (The Garden of Forking Paths), which was, in turn, included in his much-reprinted Ficciones (1944).

19. “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” is written in the form of a review or literary critical piece about (the non-existent) Pierre Menard, a 20th century French writer. It begins with a brief introduction and a listing of all of Menard’s work.

20. Borges’ “review” describes Menard’s efforts to go beyond a mere “translation” of Don Quixote by immersing himself so thoroughly in the work as to be able to actually “re-create” it, line for line, in the original 17th century Spanish. Thus, Pierre Menard is often used to raise questions and discussion about the nature of authorship, appropriation and interpretation.

21. Borges: English 1962: Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote translation history: Spanish – 1942, 1944 / French – 1951/ Italian – 1957 / English – 1962 / French – 1963 / Norwegian – 1964 / English – 1965 /Italian – 1967 / Spanish – 1970 / Estonian – 1972 / Greek – 1973 / English – 1974 / Estonian – 1976 / Portuguese – 1976 / Japanese – 1978 / English – 1980.

22. The second division of [SIC] pivots on Jorge Luis Borges’s story: “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote,” taking the publication history of the story, in all languages, and following that history through a replicated series of auto-translations.

23. Borges: English 1962: “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote” / first paragraph: The visible work left by this novelist is easily and briefly listed. They are, therefore, the omissions and additions perpetrated by Madame Henri Bachelier unpardonable in a catalog as a false newspaper whose Protestant tendency is no secret, was the ignorance to impose its readers that these are few and poor Calvinist, if not Masonic and circumcised. The true friends of Menard have viewed this catalog with alarm and even with some sadness.You could say that yesterday we gathered before his final monument, including the funeral cypress, and already Error tries to tarnish his memory …Decidedly, a brief rectification is unavoidable.

24. Borges: English 1965 / first paragraph: “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote”: The visible remains of this author are easily and briefly enumerated. They are, therefore, the omissions and additions perpetrated by Madame Henri Bach Lier unforgivable in a newspaper as a catalog of the false Protestant tendency is no secret, it is ignorance to instruct his readers that they erkalvinistene few and poor, if not Masonic and circumcised. The true friends of Menard have viewed this catalog with alarm and even with a little sadness. One can say that yesterday we gathered before his final monument, including the funeral cypress, and already Error tries to tarnish his memory … Definitely, a short correction inevitable.

25. Borges: English 1974 / first paragraph: “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote:” It remains easy to see that the author is listed and briefly. So there are omissions and additions made by Mr. Henri Bach newspaper list for the inexcusable Lier Protestant tendency is no secret, of ignorance, to give readers some erkalvinistene and bad, if not Masonic and circumcised. The true friends of Menard have dealt with the anxiety and the list just sad. We could say that we have today, before the final monument, including the funeral cypress, and already Error tries to tarnish the memory of … Of course, a brief correction inevitable.

26. Borges: English 1980 / first paragraph: “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote:” It is easy to verify that remains is that the author described briefly. Therefore, the list of additions made by the tendency of Protestant Henri Bach newspaper said Lier and inexcusable inaction is to give readers some erkalvinistene and bad, from ignorance, otherwise it is a secret Masonic and circumcised not. True friends of Menard deal with anxiety and just sad list.We are including the funeral cypress can say that we have before the end of the monument, and the attempt to color the monument already … but the error correction now inevitable.

27. The version of “Menard” included in the middle portion of [SIC] is thus a version of the story translated again and again until it becomes both recognizable and foreign from its supposed origin.

28. The “immoderate” use of sic—exceeding the normal bounds of usage—created some controversy, leading some editors, Simon Nowell-Smith[note 4] and Leon Edel, to speak out against it.[9]

29. A pathogen (Greek: πάθος pathos, “suffering, passion” and γἰγνομαι (γεν-) gignomai (gen-) “I give birth to”) or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host.[1][2] There are several substrates including pathways whereby pathogens can invade a host; the principal pathways have different episodic time frames, but soil contamination has the longest or most persistent potential for harboring a pathogen.

30. The fine-art edition of [SIC] will be packaged with such a biological pathogen, and the user or reader or viewer or subject or patient will choose to deploy the pathogen over the text. In this way, the book [SIC] will make the patient [SIC]k. This book will retail for $20,000.

31. Books may also refer to works of literature, or a main division of such a work. In library and information science, a book is called a monograph, to distinguish it from serial periodicals such as magazines, journals or newspapers. The body of all written works including books is literature. In novels and some other types of books (for example biographies), a book may be divided into several large sections also called books (Book 1, Book 2, Book 3, and so on). A lover of books is usually referred to as a bibliophile, a philologist, or, more informally, a bookworm.

32. The third book in the DEAD/BOOKS series, after BLANK and [SIC], is INK.—all dark, a smear of solid ink covering the entire book. Recall a mis-copied photocopy, embellished with a delightfully wasteful band of black ink along its too-wide margin, and then extend this over every surface of the text.

33. The fine-art edition should contain a Kindle soaked completely in e-ink, covered, if you will, with its own reading substance.

34. I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us…

35. We need the books that affect us like a disaster,

36. that grieve us deeply,

37. like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves,

38. like being banished into forests far from everyone,

39. like a suicide.

40. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.

Note: This work is an adaption from Schneiderman’s presentation on the panel “50 Ways to Break Fiction’s Future,” with Debra Di Blasi, Lance Olsen, Yuriy Tarnawsky, and c. vance at &NOW 5 at UC-San Diego, October 13-15, 2011. The text samples freely, but this is most likely evident to you already.

Bio: Davis Schneiderman’s recent novels include Drain (TriQuarterly/Northwestern), which did not win the National Book Award, and Blank: a novel (Jaded Ibis), with audio from Dj Spooky, which was not a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. His creative work has never appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Paris Review and Granta. He has not been the recipient of three Pushcart Prize awards for his short fiction, and has never been a fellow at Breadloaf or Yaddo. Recently he was passed over for a MacArthur “Genius” Grant.